To Pool or Not To Pool?

Heavy users of Uber and Lyft could be convinced to pool more. That's a good thing.

Over the past decade, on-demand mobility services have changed the way people travel. These services include app-based ride-hailing companies (also known as transportation network companies or TNCs), such as Lyft and Uber. TNCs offer flexible, on-demand rides that can supplement public transit and personal vehicles, and can lower the barriers to living car-free or car-light. However, TNCs also contribute to increasing vehicle mileage, traffic congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions, in part due to the time the vehicles spend driving without a passenger, which is known as “deadheading.”

Pooling — multiple travelers sharing a ride in the same vehicle — can mitigate some of these negative impacts. Pooling can increase the average number of passengers per vehicle mile and reduce both the total number of vehicles needed to deliver service, and the overall mileage those vehicles travel. Rather than each passenger requesting a separate on-demand vehicle that deadheads between trips, pooling enables two or more passengers to use the same vehicle. Pooling may slow down each individual traveler a bit, but if the deviations needed to pick up and drop off other passengers are relatively small, pooling can reduce total miles driven, while offering each passenger a cheaper ride in exchange for a slightly longer travel time.

The basic concept here is not new. Traditional carpooling (two to six travelers in one car) and vanpooling (five to 15 travelers in a van) have long been used as congestion management strategies in North America, with large employers historically playing a central role in encouraging and facilitating programs among commuters. Casual carpooling (also known as slugging) is another long-standing form of pooling where strangers share rides through informal regional systems, typically with dedicated pick-up or drop-off locations that serve heavily trafficked commuter routes. Slugging has thrived for decades in the metropolitan regions of Houston, Washington, D.C., and the San Francisco Bay Area, in large part due to the opportunities to save significant time and/or money by gaining access to carpool lanes and sharing driving costs such as tolls. Slugging remains more of a niche form of ridesharing because there are limited locations in the U.S. that have access to it.

In recent years, several mobility companies have launched app-based pooling services, including app-based carpooling (e.g., Waze Carpool, Scoop), door-to-door pooled on-demand rides (e.g., Uber Pool and Lyft Shared rides), indirect pooled on-demand rides (e.g., Uber Express POOL, Lyft Shared Rides Saver), and microtransit (e.g., Via, TransLoc). By offering more dynamic ride-matching services, more easily, to a larger market than traditional pooling, these new services present an opportunity to encourage pooling among a broader group of travelers.

However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic — which led to many pooled ride services being suspended — these on-demand pooling services were seldom used. The rates of pooled ride requests were so low, in fact, that most riders willing to pool often ended up riding alone. Pooling, as a result, is not living up to its promise. While data on the matter are scarce, existing research from across the U.S. suggests that — depending on the region measured — just 10% to 40% of TNC ride requests are for pools, and of those, only about 15% to 25% are successfully matched. After surveying California TNC drivers in 2018, the state’s Air Resources Board concluded that there was a negligible difference in the average number of passengers per vehicle between private and pooled trips. Because pooling requests were so infrequent, and because private requests often included more than one rider, the average pooled and private ride ended up having about the same number of passengers.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic — which led to many pooled ride services being suspended — these on-demand pooling services were seldom used. The rates of pooled ride requests were so low that most riders willing to pool often ended up riding alone. Pooling, as a result, is not living up to its promise.

Why are pooling requests so rare? Although a growing literature examines the sociodemographics of TNC users and their travel behavior, the determinants of pooling specifically are not well understood. An obvious appeal of pooling, at least in the abstract, is that it saves money. So one possible explanation for low levels of pooling is that compared to riding alone, pooling’s savings thus far have not been large enough to induce more interest. Several regions have enacted pricing strategies to encourage pooling, including surcharges on solo rides and accompanying discounts for pooled ride options. It is not yet known whether these strategies are successfully discouraging ride-alone TNC use and encouraging pooling instead. Other potential issues include the relative travel times and reliability across ride-alone and pooled options — put simply, does agreeing to pool make a ride intolerably long and/or impact a traveler’s comfort level about sharing a ride with strangers?

To investigate the opportunities and challenges for expanding the pooling market, we surveyed over 2,400 residents of the Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Diego, and San Francisco regions in fall 2018. Our sample was representative of the population in each region and included both people who used TNCs and people who did not. We asked respondents about their travel preferences, including how often they use various transportation modes (e.g., carpooling, public transit, and TNCs). In addition, we presented people with hypothetical travel scenarios (for instance, going to a restaurant/bar, going to work, or connecting to a public transit station) and asked what on-demand ride option they would prefer in those circumstances. We used all these responses to examine which groups may be the most likely to engage in pooling and might therefore be encouraged to increase their future use.

Who’s More Likely to Pool?

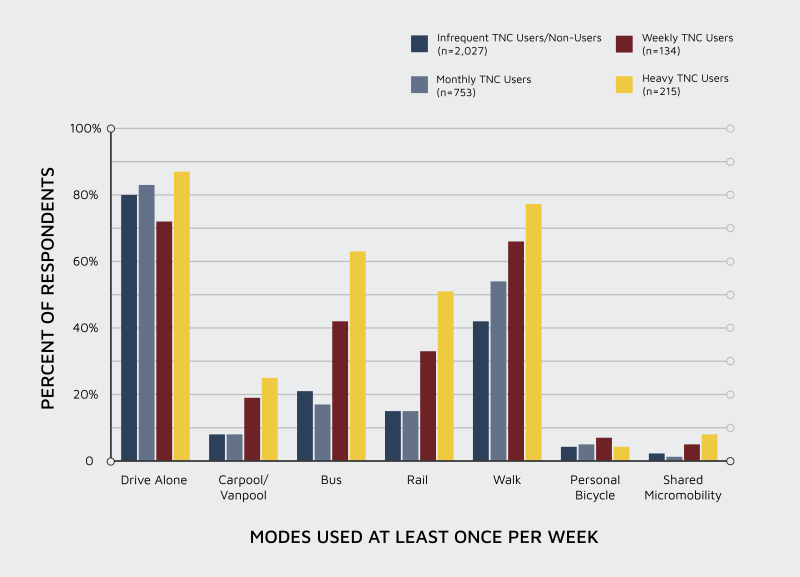

We found that TNCs present a significant opportunity to expose travelers to pooling. TNC use is far more prevalent than traditional carpooling. Across all metropolitan areas surveyed, just 10% to 15% of the population carpool or vanpool at least once a month. In contrast, about 22% to 33% use TNCs at least once a month. TNCs, therefore, represent a larger base of people who might be persuaded to pool. People who use TNCs once a week or more are more likely to be using a variety of transportation modes on a weekly basis, including carpool/vanpool, walking, public transit and shared micromobility (e.g., scooter sharing, bikesharing), than other travelers (Figure 1). More specific to our question, we also found that travelers who use TNCs, public transit, shared micromobility, or carpool/vanpool on a weekly basis are generally more likely than other travelers to choose to pool over riding alone in a TNC. This may reflect a greater level of comfort with sharing rides among travelers that already use shared modes of transportation, as well as a greater willingness to accept the uncertainty in travel time that is often experienced with such services.

Figure 1. How does weekly travel behavior differ across TNC users?

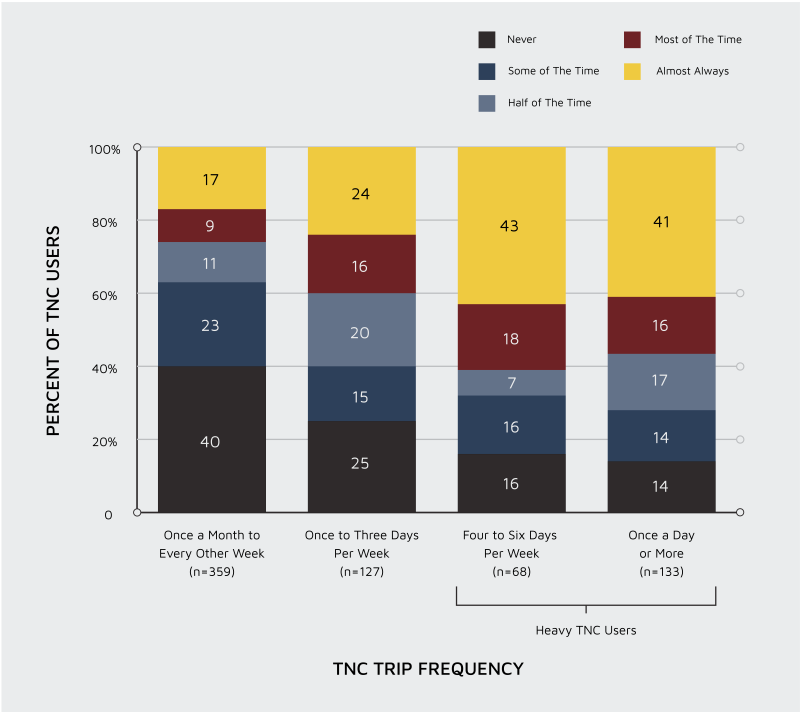

More frequent TNC users are more likely to consider pooling. Only about one-quarter of monthly TNC users consider pooling more than half the time they use TNCs, compared to about 40% of weekly users and about 60% of heavy users — those using TNCs more than three days per week (Figure 2). Heavy TNC users make up about 16% of the population in the San Francisco and Los Angeles regions, about 9% of the San Diego region, and about 6% of the Sacramento region. About 30% to 50% of these heavy users make one or more TNC trips per day, which suggests a sizable opportunity to increase pooling. An additional finding, however, is that even though heavy TNC users are most likely to consider a pooled ride option when using TNC services, they were less likely than weekly users to choose a pooled ride, in the hypothetical scenarios we presented.

Figure 2. How often do TNC users consider using pooled TNC ride options when requesting a ride?

Converting more of the heavy users from only considering to actually choosing pools, then, could boost pooling substantially. Heavy TNC users differ notably from the broader population of TNC users. Across all regions studied, heavy TNC users are disproportionately low-income, more likely not to own or lease a car, and more likely to use TNCs for essential trips, such as commuting, going to grocery stores and visiting health care providers. People with a medical condition or disability that makes it challenging to travel are also more likely to be heavy TNC users. Heavy TNC use also varies by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. In particular, the group of heavy TNC users 18 to 29 years old is primarily made up of both higher-income white and lower-income Black riders.

Across both TNC users and non-users, we found that, when presented with hypothetical travel scenarios, travelers aged 18 to 29 years, those earning less than $35,000 annually, and those owning or leasing a vehicle are generally the most likely to choose to pool. In contrast, high-income travelers who earn more than $100,000 annually are the least willing to accept any additional travel time in exchange for the cost savings of pooling. Our hypotheticals also suggest that across all regions except San Francisco, travelers are most likely to pool when choosing among on-demand ride options for commute trips. In the Bay Area – the only region where use of TNCs for commuting increases with income – travelers are even more likely to choose a pooled ride to connect to/from a public transit station.

Although our study did not explore concerns for the potential health risks of using on-demand rides and pooling, as the survey predates the COVID-19 pandemic, we find that attitudes and perceptions about interactions with TNC drivers and other passengers, as well as the environmental impacts of TNCs, are significant factors for on-demand mode choice. TNC users have more positive attitudes toward interacting with a driver and other passengers than do non-users, suggesting that these factors may pose a barrier to TNC adoption generally and across pooled rides, in particular.

Policy Recommendations

Although heavy TNC users constitute a relatively small portion of the overall population, they may be the most impacted by policies that encourage pooling, as they have already incorporated on-demand rides into their daily travel decisions. The following strategies could increase pooling among heavy TNC users while increasing general mobility and accessibility for underserved populations:

- Promotional offers for pooling to public transit stations, employment centers, and health care services. Offering a discount on a public transit fare in return for pooling to a public transit station could be an attractive strategy for increasing public transit ridership through pooled first/last-mile connections. Discounts on future rides in return for choosing a pooled ride can be particularly effective for reducing miles driven during periods of peak or abnormal congestion, such as during rush hour or a major event. Incentives to pool across multiple trips (e.g., “Take three pooled rides to get one free”) could effectively encourage heavy TNC users to try pooling, as there are ample opportunities for these already captive users to shift their on-demand ride choices with relatively low risk of inducing additional on-demand rides.

- Targeted subsidies for travelers that are low-income, unemployed, or have a medical condition/disability. Such programs may be modeled after shared micromobility low-income membership programs (e.g., Bikeshare for All), which determine eligibility by verifying participation in local, state, or federal aid programs such as CalFresh or Medicaid. It may be particularly beneficial to direct public transit discounts toward underserved communities to promote pooling, while alleviating the cost burden of heavy TNC use that may arise from poor reliability of or limited access to public transit. Mobility as a service (MaaS) or mobility on demand (MOD) strategies can be leveraged for this purpose by providing eligible travelers with discretionary subsidies for a suite of mobility services with an integrated trip planning, reservation, and payment system with incentives for pooled rides.

Indirect pooled rides offered by TNCs and microtransit providers are another opportunity to reduce congestion from single-occupant vehicle use and deadheading. Since indirect pooled rides minimize driving deviations for picking up and dropping off additional passengers (by requiring that users walk a portion of the trip and meet the vehicle), they can decrease the total vehicle travel time of an on-demand ride. Moreover, we found that able-bodied travelers in some metropolitan regions would rather walk a minute than wait a minute. Thus, by converting waiting time to walking time and reducing in-vehicle time, indirect pooled rides can be a more attractive option with co-benefits for society and the environment (e.g., less miles driven, emissions, and cost per ride). Local governments can make indirect pooled rides more attractive through:

- Curb access management, including dedicated pick-up and drop-off locations for on-demand rides in both residential and commercial zones. Dynamic curb access management systems that differentiate pricing by time of day and/or location could encourage pick-ups and drop-offs at designated locations that minimize disruption to traffic flow and improve safety, while imposing a premium on door-to-door services. Restricting TNC curb access to strategically placed pick-up and drop-off locations during peak periods can further encourage pooling by shifting wait times to walking time and increasing matching rates. Existing activity data reporting requirements for TNCs in California would facilitate the enforcement of such policies.

- Mileage-based congestion charging within a designated zone and time period would provide additional financial incentives to reduce TNC mileage and increase pooling during peak periods. While some existing congestion charging policies simply charge on a per-trip basis, a charge that is applied with respect to the miles driven within a congested area would make the price incentive for pooling even stronger. This approach could also offer an additional incentive for ride operators to minimize the mileage driven by vehicles both with and without passengers. This approach could be paired with discounted pricing for pooled rides and lower-income or otherwise underserved travelers.

Finally, there is tremendous untapped potential to increase the market share of pooling among commuters. About 40% of weekly TNC users in the San Diego region, about 30% in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area regions, and about 20% in the Sacramento region use TNCs to commute to or from work or school. Our hypotheticals showed an increased likelihood to pool for commute trips, which may reflect travelers being more willing to pool for trips if they can reliably reserve a ride in advance. This option is currently provided by app-based carpooling services, microtransit services, and TNCs in some pilot areas. All of the policy recommendations proposed above would also encourage pooling among commuters.

Overall, our research demonstrates that the growing adoption of on-demand mobility services offers an opportunity to expand the market for pooling. Whereas traditional carpooling programs and services have generally been restricted to commuters, pooled on-demand ride options are now only a tap away from the ride-alone options being used by a much broader base of travelers for a much broader array of trips. Encouraging travelers to pool when using on-demand ride services can not only reduce the overall congestion and environmental impacts of these services, but potentially increase the likelihood that they consider other forms of pooling, including microtransit services and public transit. This can trigger a virtuous cycle in which a greater portion of travelers willing to pool results in more successful matches across more similar trips, making pooling more reliable, convenient, and affordable. Heavily trafficked routes would then be more likely to support microtransit services in which larger vehicles, such as vans and shuttles, pool larger groups of travelers.

Encouraging travelers to pool when using on-demand ride services can not only reduce the overall congestion and environmental impacts of these services, but potentially increase the likelihood that they consider other forms of pooling, including microtransit services and public transit.

As the world continues to adapt and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, we face a renewed opportunity to encourage pooling among travelers, as they resume both work and recreational activity. If we do not seize this opportunity, lingering fears about the health risks of taking crowded public transit services may result in higher levels of single-occupant vehicle travel than prior to the pandemic. Although we do not yet know the pandemic’s lasting impact on travelers’ willingness to pool, or on the stability of TNC driver supply, any resumption of on-demand ride services should be accompanied by renewed efforts to encourage pooling.

Although we do not know yet what the lasting impact of the pandemic will be on travelers’ willingness to pool or the stability of TNC driver supply, any resumption of on-demand ride services would be ideally accompanied by a revitalization of efforts to encourage users to pool.

While the future landscape of pooling and shared services continues to evolve, with unexpected disruptions, opportunities, and challenges, ongoing research and innovative strategies will be needed to guide developments and to optimize the social and environmental benefits of these services. Continuing to develop a nuanced understanding of rider characteristics and use cases is necessary to develop equitable strategies that support the mobility needs of underserved communities, while minimizing the congestion and emission impacts from road transport. Notably, several metropolitan regions across the U.S. are considering congestion pricing policies that, with the inclusion of targeted discounts or exemptions and reinvestment of revenue in public transit, are expected to encourage travelers to rethink the question: “To pool or not to pool?”