What Do Residential Lotteries Show Us About Transportation Choices?

Actually, quite a lot.

People in places like San Francisco walk and take transit more, and drive less, than people in places like Los Angeles or Louisiana. To anyone who has been to these places, the reason for this difference might seem obvious: San Francisco is laid out in a way that makes walking and transit much easier, and driving much harder. San Francisco has more transit stops and more frequent transit service. It has less off-street parking. Driving in Los Angeles is the most convenient thing to do, so people do it. In San Francisco, driving is often inconvenient and expensive, so people do it less.

This reasoning is what underlies the voluminous research literature on travel and the built environment. It makes sense. It is also, however, surprisingly hard to prove. The problem arises because people, for the most part, can choose where they live, and as a result, it becomes difficult to distinguish cause and effect. People who like to walk might choose San Francisco over Los Angeles. Even within a city like San Francisco, people might choose different neighborhoods because they prefer different travel modes. So we don’t know if people started walking or riding transit because they moved to a walkable neighborhood close to frequent rail or bus service, or if they moved to that neighborhood because they are the kind of person who likes to walk more and drive less. The simple fact that people in walkable, transit-rich places such as San Francisco’s Hayes Valley neighborhood drive less does not, by itself, tell us much. We don’t know if Hayes Valley caused the behavior, or if the behavior brought people to Hayes Valley.

The simple fact that people in walkable, transit-rich places such as San Francisco’s Hayes Valley neighborhood drive less does not, by itself, tell us much. We don’t know if Hayes Valley caused the behavior, or if the behavior brought people to Hayes Valley.

Researchers have, in recognition of this problem, worked for decades and employed numerous statistical methods to try and isolate the causal impact of the built environment (such as parking availability and transit accessibility) on people’s travel decisions. But these methods typically require strong statistical assumptions, and none are completely satisfactory. In nearly any field of social science, the gold standard to identify causality is a randomized experiment. For obvious practical and ethical reasons, however, researchers cannot randomly assign people to housing units or neighborhoods, and then watch what they do.

There are situations, however, where households are effectively randomly assigned to housing. When these “natural experiments” arise, researchers are able to mimic a randomized experiment and get results we can more confidently call causal. This article summarizes our research into such a natural experiment: San Francisco’s affordable housing lottery.

An “As Good as Random” Experiment

San Francisco is one of the least affordable cities in the United States, and it has more people who need affordable housing than it has below-market-rate housing units. As a result, the city assigns its below-market-rate housing units by lottery. Our research examines the city’s Inclusionary Housing program, under which nearly all new housing developments with 10 or more units, whether ownership or rental, must set aside a certain percentage of units as affordable. These units are then made available for rent or purchase at below-market-rate prices to households with incomes below specified thresholds. Given San Francisco’s high incomes and cost of living, a two-person household earning up to $118,200, equivalent to 120% of the city’s median income, can generally qualify.

A 330-unit development, built on the former UC Berkeley Extension campus in the Hayes Valley neighborhood, includes 50 below-market-rate units allocated by lottery. Photo: Adam Millard-Ball

Demand for below-market-rate housing is immense, and the chances of winning a lottery are small — less than 2%. One lottery for 95 rental units attracted 6,580 household applicants. Given these long odds, households are unsurprisingly not selective about which lotteries they enter, and apply indiscriminately to many different lotteries. This is important for our research because some of the buildings provide parking and some don’t, and some are in more walkable, transit-accessible neighborhoods than others. We examined 107,310 applications to 59 housing lotteries held between July 2015 and June 2018, and found no evidence that people factor in parking, walkability, or transit when they enter a lottery. They are, understandably, just looking for a place to live. As a result, those who win and get a below-market-rate unit are, in effect, randomly assigned to different buildings and neighborhoods. San Francisco’s housing lotteries provide “as-good-as-random” assignment of people into homes, akin to conducting an experiment.

San Francisco’s housing lotteries provide “as-good-as-random” assignment of people into homes, akin to conducting an experiment.

Measuring Travel and the Built Environment

We worked with the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development in spring 2019 to survey residents of below-market-rate housing in San Francisco. We mailed a postcard-sized survey with a reply-paid envelope, and followed up with an email survey in English, Spanish, Filipino, and Chinese. We asked residents how frequently they traveled by different modes; and about car ownership, employment status, the location of the respondent’s workplace or school (if any), and their interactions with neighbors. We obtained 779 completed surveys, a response rate of 29%.

To learn about the buildings and neighborhoods our respondents lived in, we obtained data on parking and other project-level characteristics directly from the mayor’s office, and supplemented those data with information from permit approval records. For each project, we calculated four measures of transportation accessibility:

- Car accessibility, defined as the number of parking spaces per unit.

- Transit accessibility using the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s AllTransit performance score, which measures transit frequency and quality.

- Walk accessibility using the WalkScore company’s Walk Score metric, which is based on accessibility to retail, services, and other destinations, and which factors in some neighborhood design aspects, like block length, as well.

- Bicycle accessibility using the WalkScore company’s Bike Score metric, which works in a similar way to Walk Score but also includes bike lane provision.

From here, we could answer our research question: when people are assigned, in an as-good-as-random way, to a particular type of built environment, do they travel differently as a result?

Transit, Walk, and Bicycle Accessibility

Our survey results confirm that a neighborhood’s accessibility by transit, walking, and bicycling affects household travel decisions. More frequent transit service, for example, increases transit ridership and reduces driving, even after controlling for respondents’ household characteristics such as income and household size, as well as for the building’s parking ratio. Increasing transit accessibility from the level that exists in the Outer Sunset, a suburban neighborhood in San Francisco, to the level of that enjoyed by Potrero Hill, a neighborhood at the citywide median, would increase the share of those commuting by transit rather than by car by 6.5 percentage points. Increasing a neighborhood’s accessibility by walking or bicycling has a similar effect in increasing travel by these modes.

The Critical Role of Parking

The NEMA apartment building in the mid-Market neighborhood (left) has just over three parking spaces for every four units. Even here, however, rent for housing is separated (“unbundled”) from rent for parking; residents of the project’s below-market-rate units can choose to forgo a space, or pay an extra $100 per month for parking. Other below-market-rate housing such as the 1600 Market project (right) has no parking. Photos: Adam Millard-Ball

Although increasing transit accessibility significantly reduces driving, we found that parking has the greatest influence on travel. Access to parking has an effect on transit use three times as large as the effect of living in a neighborhood with good transit access. More parking also discourages walking by a smaller, but still statistically significant, amount.

Access to parking has an effect on transit use three times as large as the effect of living in a neighborhood with good transit access.

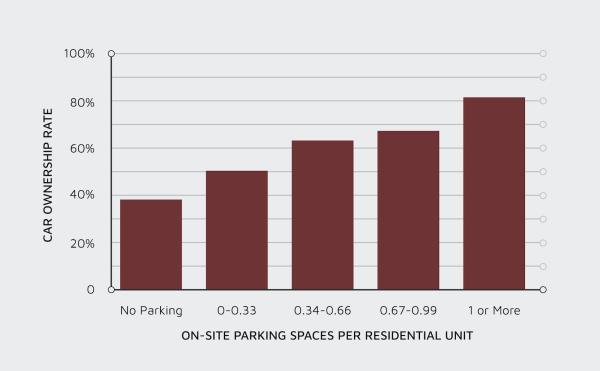

Our survey also shows that less parking leads to less car ownership and less driving. In the buildings we examined without on-site parking, only 38% of households own a car. In buildings with at least one parking space per unit, more than 81% do (see Figure 1). This impact of parking supply on car ownership remains similar even after controlling for transit, walk, and bicycle accessibility, household income, and other characteristics.

Figure 1. More parking leads to more car ownership in San Francisco

In short, the more parking that is provided, the more that residents drive, and the less they travel by public transit, walking, and cycling. Non-work trips are affected even more than commute trips — possibly because commute trips are more constrained by the availability of parking (or transit) at the workplace, and possibly because many commutes are of a distance that precludes walking or biking. In contrast, when people make non-commuting trips, such as to the grocery store, they have more choice in potential destinations (e.g., there might be two grocery stores a short distance away), and in that situation, it is the availability or not of residential parking that exerts greater influence on mode choice.

In recent years, San Francisco has made significant changes to its parking policy. Instead of requiring new buildings to provide a minimum amount of parking — typically one parking space per residential unit — San Francisco now caps the amount of parking in transit-friendly neighborhoods, often at one space for every two or four units. Our survey demonstrates how these policy changes have directly led to reductions in car ownership and driving.

Impacts on Employment

Less parking leads to less driving. That’s certainly good for the environment, but it’s natural to wonder if reducing parking implies some costs in the form of limited employment opportunities. Many jobs are inaccessible by public transit; car access could improve the chances of getting and keeping a job, and a building that discouraged residents from owning a car — through a lack of parking — could reduce those chances.

Our survey, however, showed no evidence that this trade-off exists. More on-site residential parking has no detectable impact on commute length or employment mobility (a measure of worker flexibility to change jobs). Greater transit accessibility, in contrast, has a moderately positive effect on these variables — better transit means shorter commutes and slightly more job turnover. And neither transit accessibility nor parking ratios affect the probability of a household’s members being employed full-time, possibly because of the strong economy and minimal unemployment in San Francisco at the time of the survey in 2019.

Conclusions

Researchers have long suspected that the built environment directly affects people’s travel decisions, but this intuition, while backed by a lot of suggestive evidence, has always been haunted by the fact that people choose where they live. Our research, by exploiting the random assignment of a broad variety of people into housing units and neighborhoods, gets us much closer to seeing that the built environment really does cause people to change their travel behavior. Even within San Francisco, a more walkable, bikeable, and transit-accessible city than most other places in the U.S., transit accessibility substantially affects car ownership and travel behavior. This suggests that even more substantial household responses to increased bus frequency, for example, might be expected in places where transit service is minimal at present.

We find that a building’s parking provision has an even stronger effect in shaping transportation outcomes. Because households may have several parking options — in the building, on the street, in a public garage, or in a space rented in a nearby building — one might surmise that a building’s on-site parking supply would have only a small impact on car ownership. Perhaps surprisingly, however, we show that buildings with at least one parking space per unit (as required by zoning codes in most U.S. cities, and in San Francisco until circa 2010) have more than twice the car ownership rate of buildings with no parking. If parking is provided on-site for free or at a reduced price (typically, $100 per month), then households take advantage of this amenity. In contrast, households without access to on-site parking are more likely to forgo car ownership altogether, rather than deal with the hassle of street parking or walking to a nearby garage.

Cities that want to encourage transit use and walking should consider reducing the quantity of residential parking as well as plan for alternatives to the private car. Transit accessibility evolves over decades, and a concerted effort to improve local infrastructure requires large amounts of public funding. Parking ratios, in contrast, require only regulatory changes to zoning codes: removing minimum requirements from zoning codes and possibly replacing them with a maximum. Such zoning reforms could also yield other benefits, including lowering housing costs, making more land available for new housing and commercial development, and reducing motor vehicle trips and their associated harms. Moreover, reducing space dedicated to parking appears to produce benefits without hurting employment.

Cities that want to encourage transit use and walking should consider reducing the quantity of residential parking as well as plan for alternatives to the private car.

Researchers and practicing planners have long argued that the built environment shapes travel behavior. Here, we provide the best causal evidence to date — an as-good-as-random natural experiment — to support these claims. Our findings suggest that the potential for fewer private automobile trips is large and does not depend on car-free households relocating to car-free buildings, or on people who like to ride transit moving to transit-rich neighborhoods. We show that household decisions on car ownership and travel depend on transit accessibility and walkability, but even more so on parking supply. And while we only surveyed residents of below-market-rate housing, it’s important to remember how expensive San Francisco is. A two-person household earning up to $118,200 in that city can generally qualify for affordable units. Thus, our sample includes people with a wide range of incomes, some of whom are, by most standards, quite well-off. The lesson is clear: Where streets are relatively walkable and transit service is frequent, parking emerges as the key factor shaping household travel behavior — and parking is a factor that is highly amenable to low-cost policy reforms that can rapidly provide benefits.

Acknowledgment

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies with funding from the Road Repair and Accountability Act of 2017 (Senate Bill 1). The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the State of California in the interest of information exchange and does not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the State of California.