Is Accessibility Evaluation Ready for Prime Time?

Using mobility as a proxy for access has its flaws. But how do you measure accessibility?

The basic function of transportation systems is to enable access: Travel connects people to their desired destinations, and businesses to their workers, suppliers, and markets. A new generation of tools aims to inform the work of transportation engineers, planners, and policymakers by making access easier to measure and evaluate. We reviewed the burgeoning array of access measures, and considered their readiness for transportation engineering and planning practice.

For much of human history, there was little need to measure access. Residents of pre-industrial cities often lived and worked in the same place. Even for those who worked outside of the home, jobs and most other daily needs were typically within walking distance. Cities of the era were mostly small, compact, and had little separation of land uses, because people had to get where they were going by foot.

For much of human history, there was little need to measure access.

Over the past two centuries, a series of transportation technology breakthroughs, as well as advances in building technologies, lighting, and sanitation, enabled cities to grow up and out. First the horsecar (a horse-drawn wagon on tracks), and then electric streetcars, elevators, and especially automobiles permitted faster travel and bigger cities. The car’s preeminence is hard to overstate. In the U.S., just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, walking to destinations was the second most common personal travel mode, but still accounted for only one in 10 trips. More than eight in 10 trips, in contrast, were by motor vehicle, making the automobile by far the most common way for people to get around.

To achieve this car dominance, cities have spread out for more than a century, and lots of roads and parking have been added to make it easy to drive to most destinations. These changes increased mobility, or the ability of people to move about. Today, the land use and transportation system in most U.S. cities makes it easy for those with automobiles to travel quickly to far flung destinations: to jobs, grocery stores, health care, social and recreational activities, and so on.

Transportation planning in the U.S. has long been oriented toward delivering access via mobility. While mobility can increase access for households and firms, more mobility doesn’t automatically mean better access. For example, planners have traditionally evaluated land development and transportation project proposals based on metrics that prioritize reducing nearby traffic delays. This mobility-centered analytical bias has helped keep development densities low, roadways wide, and parking plentiful. This has discouraged higher-density developments that would push trip origins and destinations closer together, and make it easier to walk, bike, or ride public transit.

Concerns over the consequences of mobility-based planning are not new, nor are calls for a turn toward planning for accessibility; both date back at least a half-century. But the push to reform planning and reorient it around access made scant progress until recently, when significant increases in data and computing capacity spurred advances in measuring and evaluating access.

To assess the current state of access planning, we reviewed research on accessibility metrics, and examined 54 different access measures proposed by researchers. We focused in particular on readily available planning decision support tools, which are both commercially developed software suites and open-access tools. We also interviewed planning practitioners in California, Hawai’i, Virginia, and those with a national scope who are among the first to test and deploy these measures in practice.

How Does Mobility Relate to Accessibility?

Mobility is the ability to move about, while access is the ability to get what you need. If a customer walks 500 meters to shop at a grocery store, and another spends about the same amount of time driving 5 kilometers to that same store, each enjoys similar levels of grocery store access, but the second customer is 10 times more mobile than the first. So while mobility is an important component of accessibility, it is not the only one. Proximity> is another important determinant. Proximity enabled the first customer to access the grocery store without traveling very far or having to drive. But access doesn’t end there. Connectivity also matters. Imagine a third customer who used the Internet to search, select, and pay for groceries, and have them delivered to their home. This customer also has access to groceries, despite not traveling at all.

Mobility is the ability to move about. Access is the ability to get what you need.

Access is thus a more encompassing (and complex) concept than mobility. It focuses less on the means and more on the ends (destinations) of travel. It is also a bigger challenge to measure and evaluate, in part because of its multifaceted nature. While mobility-based metrics focus on things like vehicle movements and traffic delays, they don’t consider the advantages of proximity. By contrast, analyzing a person’s access to education, employment, or health care entails, at a minimum, considering mobility, as well as proximity and connectivity.

While mobility, proximity, and connectivity combine to determine accessibility, there are typically trade-offs among these factors: More of one may diminish another. For example, when many origins and destinations are clustered together in dense urban districts, average travel distances are short, making it easier to walk, bike, and ride public transit to destinations. But such environments also tend to have less space available for driving and parking, so drivers frequently experience traffic delays during their trips and pricey parking at their destinations, which combine to inhibit their mobility (and, in turn, access) via car.

How easily people can reach desired destinations also varies by traveler attributes, such as whether one has access to a car, feels safe riding public transit, or has a disability that affects their ability to travel. More broadly, access is not simply an objective construct, but depends as well on travelers’ preferences, constraints, access to various means of travel, as well as perceptions of convenience, comfort, and available destinations. For instance, if a traveler is not aware of restaurant options in an unfamiliar neighborhood, her personal access to prepared food may be low, even if nearby restaurants are objectively plentiful.

Access also has a temporal aspect. People schedule their activities based on the time available to them. They typically sort flexible activities, like grocery shopping, into the times and locations available to them after performing activities with fixed times and locations, like working or going to school. The temporal availability of opportunities also affects access. You might crave pancakes at 3:00 a.m., and in a dense urban environment you are more likely to live near a 24-hour diner. But if your local diner closes at midnight, the fact that it is nearby doesn’t matter at 3:00 a.m.

Other factors, such as public transit reliability, the price of gas, transportation network delays, and policies (such as parking charges) affect access as well.

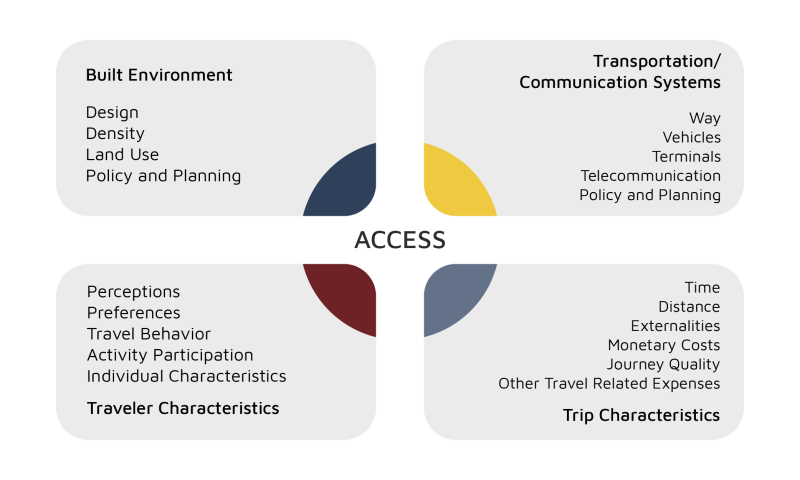

Figure 1 depicts many of the factors that go into determining access. Because of its overarching nature, access offers a powerful framework for us to think about the physical layout of cities and the opportunities they offer. At the same time, however, the multidimensional nature of access makes it harder to operationalize. We turn to this challenge next.

Figure 1. A conceptual model of the factors affecting accessibility of individuals

Operationalizing Access

Access analysis metrics and tools can operationalize access in two ways: 1) the accessibility of places and 2) the accessibility of people. Place accessibility is generally the easier of the two to measure, and place-based measures are more common as a result. Place access considers primarily the spatial arrangement of potential trip origins and destinations (residences, jobs, etc.) and the transportation networks that link them. Place-based measures allow planners and engineers to analyze accessibility at various geographic scales, such as in larger-scale, longer-term metropolitan growth projections, or smaller-scale accessibility analyses of specific land development or transportation projects.

There are limits to this approach. When we speak of a neighborhood as having more or less access to, for example, health care, we tend to treat everyone in it the same. But health care access is also affected by whether someone has access to a car, health insurance, and so on. So health care access can vary dramatically from person to person, even among people living next door to one another.

To address this, people-based access measures include the attributes and attitudes of travelers, in addition to the place-based characteristics of where they live or work. They allow us to measure access equity across types of travelers, but typically require more data than measuring how access varies across places.

Most accessibility measures offer insight on how land use and transportation systems interact, usually by determining baseline accessibility levels and then analyzing how those levels would change if some aspect of the land use or transportation system changed — such as if a new apartment project were completed, or a new rail transit stop opened. Most measures can compare and contrast alternative future scenarios; the simplest ones count the number of available opportunities within a certain distance and/or travel time threshold (e.g., a person can reach 1,000 jobs in a 20-minute walk) and compare the result with some desired policy goal.

More sophisticated tools account for individual preferences and/or socioeconomic characteristics of travelers, and assign weights to destinations based on distance, and include the temporal dimensions of access as well. For example, if a household has two pharmacies nearby, one a 10-minute drive away, and a second one a 20-minute drive, the first will be weighted more heavily than the second (even though both are within a 20-minute drive).

These access measures allow analysts to examine how equity is affected by particular land use and transportation network configurations. For instance, while people with cars may easily travel to low-density suburbs where trip origins and destinations are dispersed, access to those same developments for those without cars is much lower. Most access measures allow us to analyze these varying effects. Planners can also use these measures to analyze how various land use and transportation configurations affect opportunities for social interaction.

Accessibility analyses of larger-scale, longer-term metropolitan growth scenarios in regional planning are gradually becoming more commonplace, while more microscale, project-level analyses of accessibility remain comparatively rare. Indeed, only a few of the measures we reviewed are intended for land development or transportation project evaluation.

The more dimensions an accessibility metric incorporates, the more data it needs. Measuring access, therefore, has been greatly helped by the increasing availability of new and innovative data sources with far more detailed and nuanced information on travel behavior and access to opportunities, including in real-time. It is now possible to track travelers’ movements in exquisite (and often invasive) detail with mobile device global positioning system (GPS) data. Using social media data, we can infer trip purposes and preferences. General transit feed specification (GTFS), automatic vehicle location (AVL), and automated passenger counter (APC) data provide us with detailed information on public transit service and use.

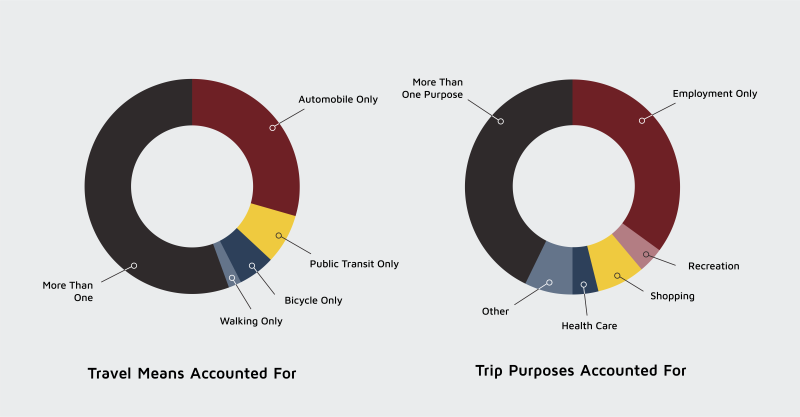

Despite this explosion of new data, many of the accessibility tools developed to date are still rather simplistic, evaluating only a particular trip purpose, a specific time of the day, or a single mode of travel. As Figure 2 shows, about one-third of the metrics we reviewed measure only accessibility to jobs (35.2%) and/or travel via motor vehicles (29.6%), though most of the commercial and open-source tools being gradually deployed in practice account for multiple means of travel.

Figure 2: Accessibility metrics and tools by means of travel, and trip purposes accounted for

Despite this explosion of new data, many of the accessibility tools developed to date are still rather simplistic, evaluating only a particular trip purpose, a specific time of the day, or a single mode of travel.

How Are Access Measures Being Applied in Practice?

We interviewed planning practitioners to learn more about their experience using accessibility tools. Most of the planners and engineers we spoke with raised concerns about both the complexity and opacity of the available tools, as well as the lack of in-house technical expertise in their organizations to use them effectively. One of our interviewees described accessibility measurement tools as “black boxes.” Others echoed similar concerns about the low user-friendliness of the tools and how hard it is to understand the background calculations that yield the output. Even those who were otherwise enthusiastic about moving to access analyses in their transportation engineering and planning work found the tools complex to use and difficult to explain.

On the other hand, most of the practitioners we interviewed also expressed concerns that the access tools they currently use are not conceptually complete; that they fail to take into account many important dimensions of access. Despite these concerns, they also worried that if they tried to adopt more sophisticated measures, they would be even more difficult to interpret, let alone explain to elected officials, journalists, and community members.

Previous studies of the contrasting perspectives of tool developers and users suggest that tool developers often do not understand the specific needs of practitioners, while practitioners frequently do not understand the underlying logic and structure of the accessibility tools or how to properly use them. As a result, enthusiasm for accessibility planning has considerably outpaced its deployment in practice, both in the U.S. and globally. To help address the problem of practitioners’ unfamiliarity with accessibility evaluation tools, two accessibility evaluation how-to manuals for planners have been recently published: “The Transport Access Manual” and State Smart Transportation Initiative’s “Measuring Accessibility: A Guide for Land Use and Transportation Practitioners”.

Despite these challenges, many metropolitan planning organizations have adopted accessibility-oriented goals in their regional transportation plans, though many of these early adopters lack access-related performance measures of goal attainment and too often conflate mobility and access-oriented criteria. At a more local level, accessibility impact analyses are, to date, only rarely employed by governments in their evaluations of land development or transportation project proposals. Some notable exceptions include the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) of Virginia’s Smart Scale initiative and the Hawai’i Department of Transportation’s Smart Transportation Rank Choice (SmartTRAC). Both of these evaluation processes include accessibility to jobs and other destinations as criteria in prioritizing projects for funding. For example, Virginia CTB assigns weights to three different accessibility factors (60% for accessibility to jobs, 20% for accessibility to jobs for disadvantaged populations, and 20% for projects promoting multiple means of travel) to calculate the accessibility score for the Smart Scale initiative.

Looking Ahead

The 54 accessibility metrics and tools we reviewed run the gamut from rudimentary to more comprehensive. Though we see significant progress in the development and refinement of accessibility metrics over the past quarter century, none yet stands out as the obviously superior choice for either macroscale regional planning or microscale project evaluation. Most of the accessibility evaluation measures we reviewed have been developed by and for researchers; only five are commercially developed or open-access tools ready for applications in practice, though we expect this number to grow substantially in the years ahead.

Although extensive data requirements and institutional inertia surely inhibit the shift to accessibility-focused planning, the tools themselves are for the most part still evolving and improving. In the course of this evolution, researchers and software developers are gradually accounting for many of the most salient dimensions of accessibility. As more jurisdictions incorporate accessibility measures into their plans and policy documents, we expect the pace of accessibility tool improvements to quicken.

Access is a powerful, even beguiling concept, but one that has proven stubbornly difficult to put into practice.

Access is a powerful, even beguiling concept, but one that has proven stubbornly difficult to put into practice. It can allow planners to focus more on the ends of transportation (destinations) than on the means (traveling). It considers land use and transportation systems as a piece, and can allow us to consider how accessibility varies across places, as well as people. After years of research, commercial access measurement tools are beginning to trickle into practice. But old habits die hard, and years of legal precedent privilege established measures of mobility over emerging measures of access. So while the access revolution has clearly begun, it remains far from complete.

So while the access revolution has clearly begun, it remains far from complete.