Where You Go When Your Car is Home

When housing precarity meets parking policy

On any given night, around 66,000 people experience homelessness in Los Angeles County. Most Angelenos are familiar by now with images of tents and sidewalk encampments. These forms of homelessness receive most of the media’s attention, but they don’t paint a full picture of the county’s homeless population. An estimated 39% of L.A. County’s unsheltered population lives in vehicles, and that share is growing. Between 2019 and 2022 alone, the number of people sheltered in cars, vans, and RVs rose 17%, from 16,500 to 19,400.

Despite this proliferation of vehicular homelessness, relatively little is known about it. In particular, there is sparse information about where people live in cars and how cities respond when they do. In part, this uncertainty arises because vehicular homelessness blends in better. Tents on sidewalks are hard to miss, but people living in cars often hide in plain sight, and, for the most part, they can move when necessary. The uncertainty also arises because governments can regulate vehicular homelessness with policies that, at least superficially, have nothing to do with homelessness at all. Most forms of homelessness are regulated via policies that directly prohibit or criminalize homelessness itself, such as ordinances that prohibit tents, or that ban sleeping outside in particular locations (like under freeway overpasses or near schools). Vehicular homelessness, in contrast, can be regulated with curb parking ordinances, and curb parking ordinances have purposes beyond the regulation of homelessness. A law that prohibits overnight parking might also be intended to facilitate street cleaning or something less transportation-related, like excluding people living in their cars. However, laws that aren’t aimed at vehicular homelessness can still affect it. In this study, my colleagues and I looked at how these regulations influence where people living in cars choose to locate.

Vehicular homelessness isn’t unique to Los Angeles. Many people experiencing homelessness, especially in West Coast cities, live in vehicles. Estimates range from 17% in San Jose, California, and 19% in Seattle and King County, Washington, to 29% in Sonoma County, California. A car is often shelter of last resort for housing-insecure people. If a person loses their housing and has a vehicle, that vehicle can prevent them from living on sidewalks and other public places. Tents and other makeshift shelters can offer protection from the elements, but cars tend to offer more safety and stability, and more mobility. A car can be locked to secure one’s belongings, blends into the neighborhood in ways a sidewalk tent doesn’t, and offers a way to reach jobs, schools, and services.

These advantages are relative in that living in a car is better than living on the street, but cars are still temporary and inadequate housing. Most vehicles have cramped conditions, and people living in them rarely have access to running water, electricity, or restrooms. People living in vehicles also incite hostility from nearby housed residents and businesses, who may be concerned that unhoused people will dump trash or waste or believe unhoused people threaten public safety. These hostilities and fears aren’t unique to people in vehicles — neighbors often have the same worries about tents and encampments — but residents may also begrudge the use of scarce parking spaces, or use a concern about parking spaces to trigger government action against the people experiencing homelessness.

The main driver of homelessness is the lack of housing. But vehicular homelessness is also a transportation issue, as the immediate response from cities often involves regulating cars and streets. Complaints about people living in cars can lead to calls for new laws that criminalize using a vehicle for housing or for increased enforcement of existing laws. These laws might directly ban sleeping in cars or more indirectly ban overnight parking. They might apply citywide, or only in certain neighborhoods. Such rules make it difficult for unhoused people to find safe parking and increase their likelihood of being towed, ticketed, or having an encounter with the police. Cities can ban overnight parking for multiple reasons, but it seems fair to assume that in many cases the goal of these regulations is to ensure that people living in cars go someplace else. Our goal in this research was to determine if more regulated places did see fewer people living in cars. We did so by documenting vehicle regulations in different places and then correlating those regulations with the presence of people living in cars.

Cities can ban overnight parking for multiple reasons, but it seems fair to assume that in many cases the goal of these regulations is to ensure that people living in cars go someplace else.

Counting vehicular homelessness and the laws that regulate it

Each year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development requires local homelessness agencies to count the number of people experiencing homelessness. These “point-in-time” counts, as they are called, provide the basis for federal funding to these agencies. Counts also help service agencies understand geographic patterns, like where people experiencing homelessness live and cluster or whether investments in permanent housing reduce the number of people living outdoors.

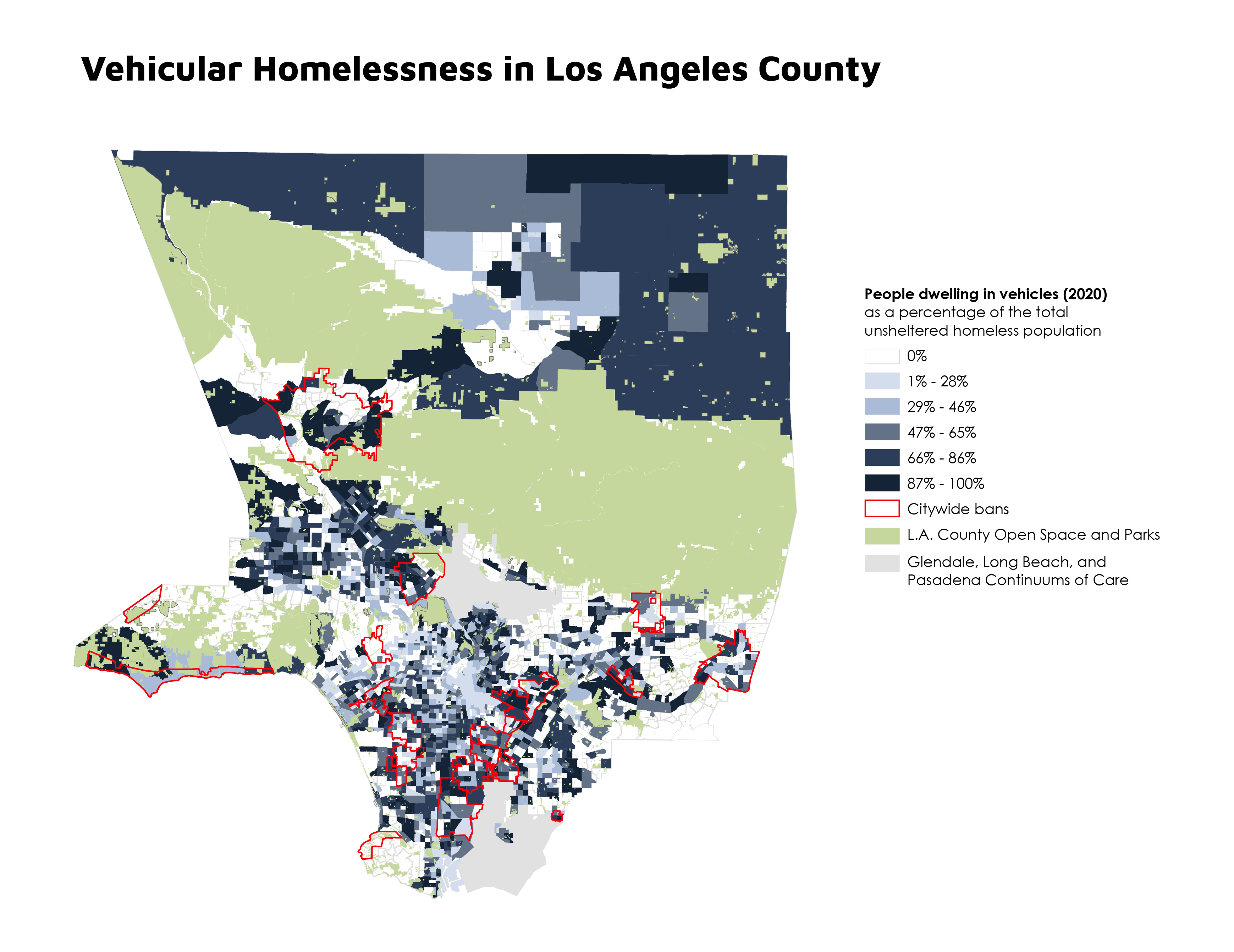

We used the January 2020 count conducted by Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, or LAHSA, which is the agency responsible for homeless services in almost all of L.A. County (the exceptions are the cities of Glendale, Pasadena, and Long Beach). LAHSA collects more detailed data than is required by the federal government, breaking down the counts by the type of shelter, including sheltering on the sidewalk, in tents, cars, vans, or RVs. They also collect and share these data by census tract, which allowed us to see how the homeless population is geographically distributed. We also drew on older count data from 2016 to try and capture how this population has grown and changed over time.

We use these data, along with information we assembled about local land uses and local homeless services, to test some ideas about how people experiencing vehicular homelessness decide where to live. We suspect, for example, that to avoid complaints from housed people in residential areas, people living in cars might try to locate in nonresidential areas — such as census tracts with greater proportions of freeways, industrial land, or parks. We also imagine that people living in cars might also want to stay close to homeless services, and thus be more likely to locate in tracts where more services are available.

Regulations could impede these desires. In addition to knowing where people in cars live and the land uses within those areas, we needed to know where and how cities regulate vehicular homelessness. To assemble data on these regulations, we searched through local laws in the 85 cities and unincorporated L.A. County that fall within LAHSA’s jurisdiction, looking for rules that would regulate vehicular homelessness both indirectly and directly.

We consider indirect regulations to be laws that require vehicles to be moved after a period. The most prominent indirect regulation is a California state law that requires all vehicles to move every 72 hours. This means anyone living in a car must change location every three days, assuming the law is enforced. Notably, the extent of enforcement by local authorities is an open question. Many cities have augmented this baseline state regulation, and issued prohibitions including:

- No parking at certain times of day, most specifically overnight.

- Prohibitions based on vehicle size typically targeting RVs.

- Combinations of the two, meaning banning oversized vehicles overnight.

Local governments might issue these rules to cover entire cities, or (more commonly) vary the rules by area or block.

Cities can also indirectly regulate vehicular homelessness through permit parking districts. While permit requirements do not explicitly ban people from sleeping in cars, drivers can’t get a permit without submitting proof of a residential address in the district, which unhoused people obviously lack. For people experiencing homelessness, a permit district thus makes living in a car de facto illegal.

Direct regulations, in contrast, are rules explicitly aimed at restricting people living in their vehicles. These include restrictions on people sleeping in cars. As with indirect restrictions, these direct restrictions often varied substantially within cities. Some cities restricted sleeping in vehicles in specific residential areas, streets, or business districts. We call these rules “zonal restrictions.” For example, the City of Los Angeles outlaws sleeping in cars on particular streets, and the City Council regularly expands the list of streets where sleeping overnight is banned.

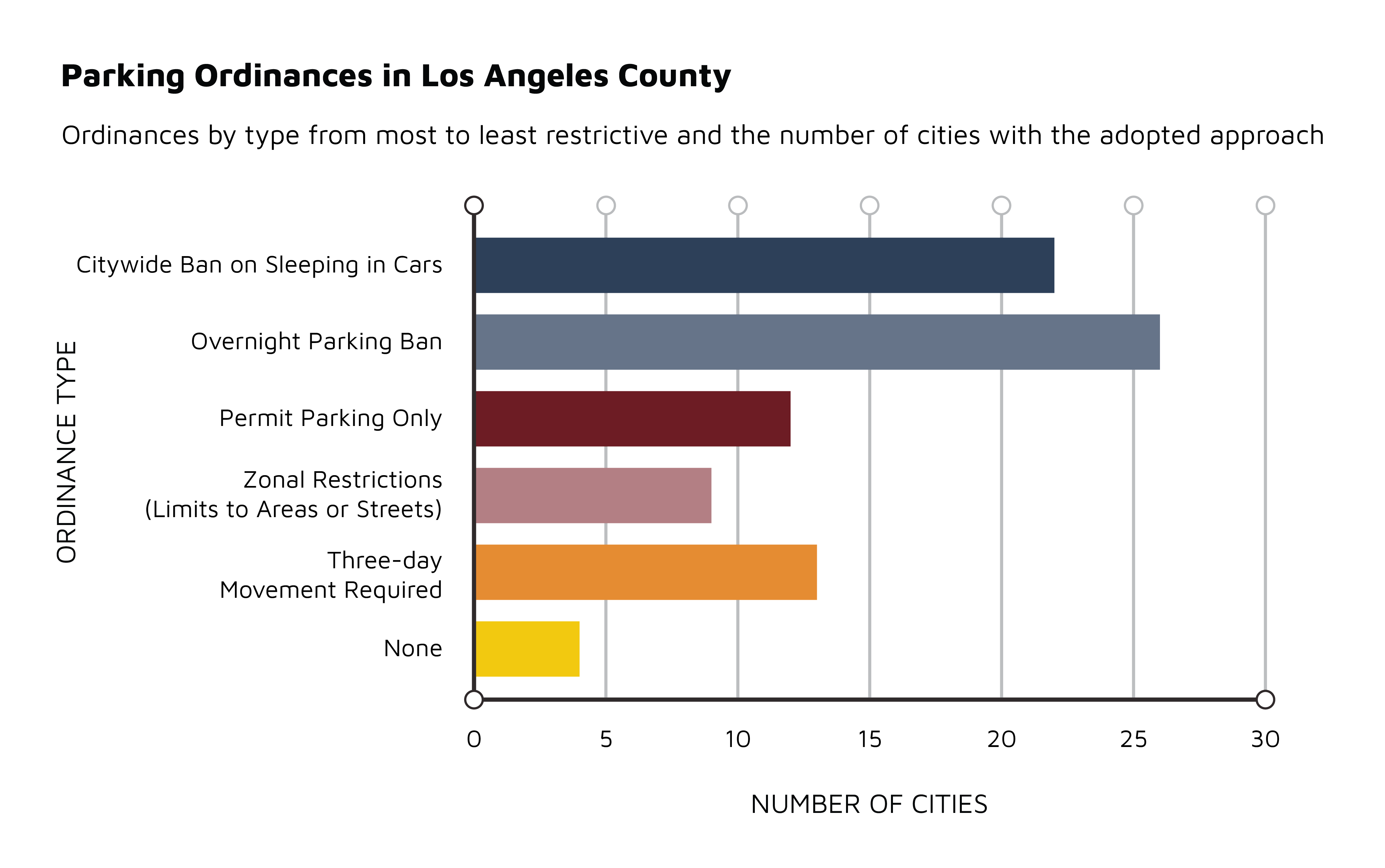

Figure 1 shows the results of our regulation research. Nearly everywhere we looked, cities had enacted some type of ordinance that regulated people living in cars. Citywide bans on sleeping in vehicles and overnight parking bans were the most common approaches. Fewer cities used permit parking or zone restrictions. A small number of cities made a point of reiterating, as a local ordinance, the statewide mandate to move a car every three days. Only four cities had no local regulations listed. The majority of the ordinances we found were not new; most cities had enacted them before 2016. The age of the laws might mean they weren’t originally intended to target homelessness, but we can’t say that for sure. For example, homelessness in L.A. got much worse after 2016, but was a serious problem before that as well. Even laws originally passed for other purposes, moreover, could be easily repurposed as anti-homelessness ordinances. And some areas had recently made their laws more restrictive: Notably, eight of the 22 citywide bans against sleeping in cars had been written or amended since 2016.

We conducted statistical analysis of where people were living in their cars, and much of what we found was straightforward and expected. Larger census tracts had more vehicles than smaller tracts. Tracts with more industrial land had more people living in vehicles, as did areas with homeless shelters.

What about regulations? Nearly all the vehicles with people living in them were parked in cities with some type of regulation against living in a car. How these regulations relate to the presence of vehicular homelessness, however, is less clear or straightforward. For example, in the eight cities that passed citywide bans on sleeping in cars since 2016, the number of people doing so had more than doubled since the 2016 homeless count. We could interpret this evidence multiple ways: vehicular homelessness may spur regulation, regulation may be ineffective at preventing vehicular homelessness, or some combination of both.

Our statistical analysis helps clarify some of these relationships. We found that places with strict regulations, like citywide bans on sleeping in cars or bans on overnight parking, had fewer people living in vehicles than places where restrictions were less severe. This finding isn’t the whole story of how regulations work.

Cities aren’t islands. A regulation that reduces vehicular homelessness in one place might also influence it in another nearby place. Our analysis found evidence of such a spillover effect. While cities in Los Angeles County with the strictest regulations — citywide or overnight bans — saw a decrease in vehicles in their cities, the neighboring areas with weaker regulations saw a rise. The nearby increase, in fact, exceeded the local decrease. Strict regulations were associated with less vehicular homelessness in the regulated area, but more vehicular homelessness just outside it.

Cities aren’t islands. A regulation that reduces vehicular homelessness in one place might also influence it in another nearby place.

Safe parking alternatives

Many cities respond to people living in cars with citywide bans on sleeping in vehicles and other strict policies. Ongoing trends, along with our research, suggests little reason to believe these approaches are working. The number of people living in cars continues to rise, and while some regulations reduce the presence of vehicular homelessness in certain areas, our evidence suggests that they move the problem rather than solve it. The ultimate goal of homelessness policy should not be to move or hide it, but to end it, through permanent housing.

Permanent housing, unfortunately, is unlikely to arrive in the short term. Los Angeles has for years been unable to deliver permanent housing at a pace that meets the need. Cities thus need to adopt short-term approaches that prioritize the well-being of people living in cars. Homelessness is a terrible situation, and creating and enforcing regulations as the first response can make people’s bad circumstances even worse. Citing and towing vehicles that people are living in does not reduce homelessness; it only increases the precarity of unhoused people.

A better approach could involve ensuring that people have safe, legal places to sleep in their cars while they find approaches for permanent housing placements. Safe parking programs, use parking lots to provide legal, secure shelter and bathroom access to people living in cars. The parking lots can also become places where unhoused people receive services and counseling on the pathway to permanent housing. A recent nationwide review found these programs to be a “stabilizing force” in people’s lives.

Santa Barbara was the first city to offer safe parking as an intermediate solution for people living in vehicles. The New Beginnings Counseling Center launched a safe parking program in 2004, and now manages 26 lots throughout Santa Barbara County. In addition to legal overnight parking and bathrooms, New Beginnings provides rapid rehousing for unhoused people, as well as case management, employment services and food assistance. Because people living in cars are dispersed throughout cities and often must move, consistent contact with a caseworker is difficult to maintain. By linking people to social workers at their parking sites, New Beginnings has successfully transitioned over 1,000 people living in cars into permanent housing.

Safe parking began in Los Angeles in 2017, and today the city makes 17 lots available. Like New Beginnings, the nonprofit organizations that run the L.A. sites offer restrooms and showers, laundry service, and donated food. They also connect residents with caseworkers who provide health and mental health referrals and services, enrollment in entitlement programs such as unemployment and social security, and get people on the pathway to permanent housing. Some sites also provide cash support for car repairs or DMV registration fees.

While they are a harbor in a storm, safe parking programs generally can leave more to be desired. Most safe parking lots don’t allow RVs, which would leave out one-third of the people living in vehicles in L.A. The hours of operation can also pose a challenge. Typically, lots open between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m., and occupants must leave by 7 a.m. or 8 a.m. the following morning. Following a two-year safe parking program evaluation, San Diego approved three sites to operate 24 hours a day and specifically target newly unhoused people, older adults, and families with children.

Safe parking is not an easy sell to local communities, even as neighbors want something done about people living in vehicles. Housing for people experiencing homelessness often faces neighborhood opposition and safe parking programs are no exception. When a safe parking lot in L.A.’s Westchester community was up for renewal, nearby residents protested. The lot was renewed, but its capacity was reduced. Such opposition may explain why the number of safe parking lots pales in comparison to the number of people living in their vehicles. Additionally, the presence of safe parking lots has been used to justify increased enforcement of regulations prohibiting sleeping in cars on the streets. For example, people parked nearby but not inside the Westchester safe parking lot are subject to being towed if they stay overnight.

Just as people living in cars use their vehicles as temporary homes, safe parking programs represent a way to use vehicle storage spaces as a refuge. Cities could use their abundant off-street parking lots to create these spaces. The City of Los Angeles alone owns nearly 12,000 public parking spaces. Los Angeles County contains some 18 million parking spaces. Using a fraction of these parking spaces for safe parking could accommodate all of the people in need. Right now, however, across Los Angeles County, there are currently 17 safe parking sites that can collectively serve 508 people. This program is a drop in the bucket for a population of nearly 20,000 people living in their vehicles.

Making it easier to live in a car isn’t a long-term solution and doesn’t address the deeper structural issues that produce homelessness. But neither is the current system of enacting and enforcing regulations — it only makes people move around searching for areas with weaker regulations. Carefully implemented approaches to address the short-term needs of people living in vehicles demonstrate promise and can provide paths toward helping people get housed. Ultimately, cities ought to use their transportation policies and assets to provide stability and safety on the road to a better future for people experiencing homelessness.