A Nudge Toward Greener Flying

One simple trick to lower our carbon footprint

Air travel now accounts for about 3% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, and the sector’s emissions are rising: Global air travel more than doubled from 2004 to 2019. This is literally a first-world problem — most people on Earth fly rarely, if ever. By some estimates, the 1% of humans who fly most often are responsible for half of all air travel emissions.

The good news is that even small changes in the behavior of those of us who do fly a lot (and the organizations that employ us) can have a noticeable impact on emissions. We’ve been researching how changes to the websites consumers use to purchase airline tickets could guide them toward lower-emissions travel decisions. This research has turned out to be very timely. About a year ago, Google Flights added emissions information to its flight search interface, and our research suggests that this addition could have a small, but consequential, effect on global air travel emissions.

Posting emission information is not a panacea. Eventually, air travel will have to be cleaned up, but aviation is one of the most difficult sectors to decarbonize. Airlines are already buying some electric planes for short hops, investing in biofueled aircrafts for longer hauls, and hydrogen is a possibility in the longer term — but most benefits from these investments will come in the future. In the meantime, personal choices to “fly greener” can reduce individual and institutional carbon footprints and, in turn, encourage airlines to provide “greener” flights.

A complex problem

Picking a low-emissions flight can be tricky. Even with our current fossil-fueled planes, flights with the same origin and destination can have very different carbon footprints. Newer planes, like newer cars, are more fuel-efficient. Long-distance flights have to carry more fuel per passenger, but an itinerary with more connections requires more fuel because take-offs, circling, and landing are all energy-intensive. Itineraries using different connection cities will be different lengths. The number of passengers can matter too: On a crowded flight, or an all-coach airline, we can take comfort in using less fuel per passenger.

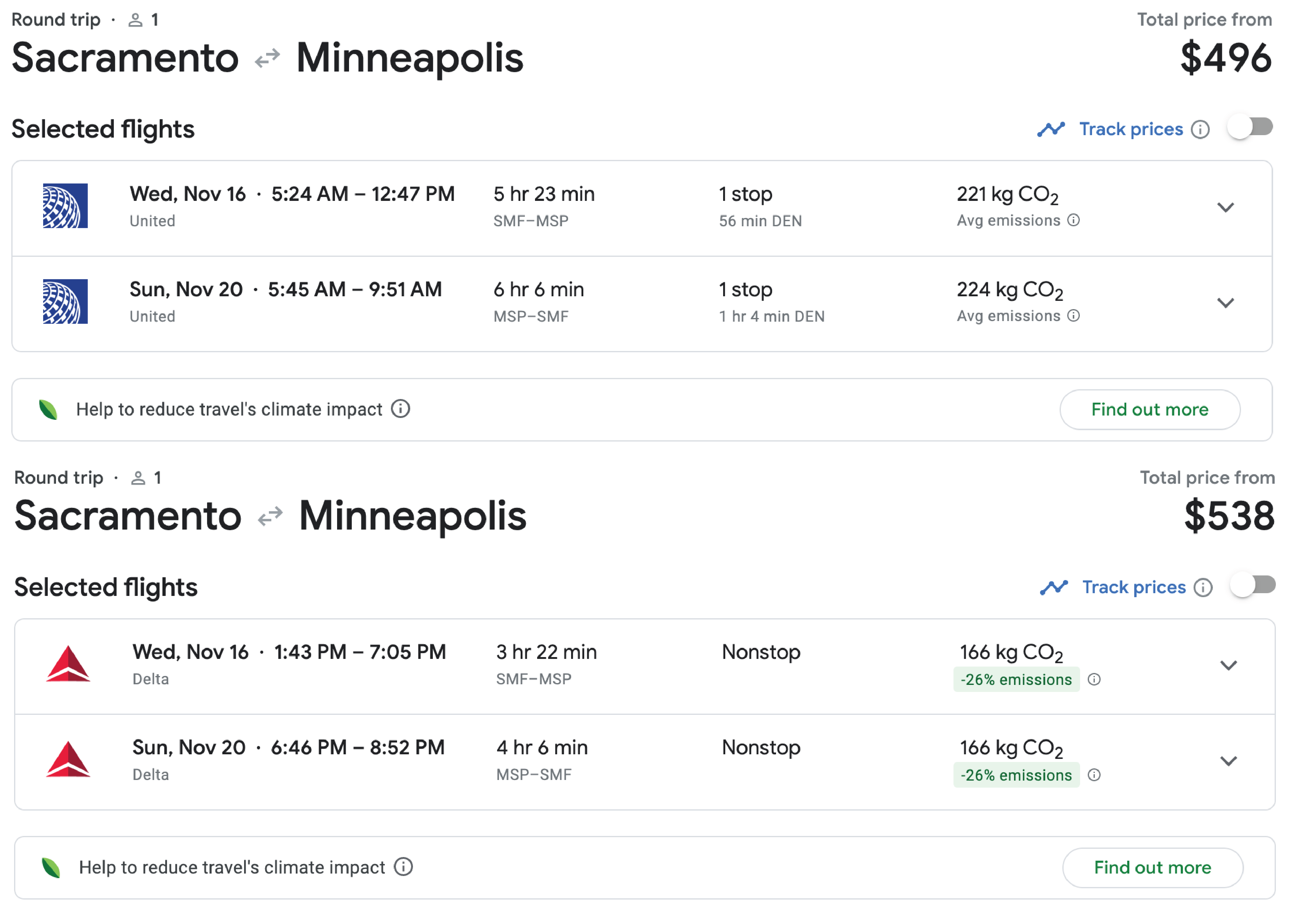

For example, Google Flights estimates that a less efficient round trip with a layover itinerary from Sacramento to Minneapolis might produce 113 kilograms more emissions than a more efficient nonstop flight, and that one round trip from San Diego to Venice, Italy, might produce 557 kilograms more than another, even though both flights have two layovers (Figures 1 and 2).

In addition to burning fossil fuels, airplane exhaust contributes to warming in other ways. Airplane vapor trails help trap heat, and planes emit other non-CO2 gases and particulates into the upper atmosphere. As a result, a pound of fossil fuel burned from a plane in flight has a greater warming effect than a pound emitted from the tailpipe of a car. Exactly how much greater remains a difficult scientific question; estimates range from a factor of 1.3 to 2.7 or even more. Somewhat controversially, Google Flights has opted to show emissions estimates that do not include these other warming pathways. To account for this, in our research we multiply fuel-burn emissions by 2.0, and we recommend doubling Google Flights estimates when comparing the emissions of a flight to other lifestyle emissions estimates.

For example, in the Sacramento–Minneapolis comparison above, where Google estimates a 113-kilogram difference between two flights, we would double this figure to a difference of 226 kilograms, or close to 5% of the average American’s annual transportation carbon footprint (about 4 tons per year). In the San Diego–Venice example, doubling the estimated 557-kilogram difference between the two flights indicates that the less efficient flight adds an extra ton of emissions to your personal carbon footprint, the same difference that would arise from an average year of driving a 25 mpg car (say a Ford Explorer) instead of a 33 mpg one (like a Toyota Corolla). Not taking the Venice trip at all, of course, might cut your annual transportation emissions in half.

For cars and appliances, research has shown that when people can see energy efficiency information while they shop, they are more likely to take energy efficiency into account. Could the same be true of flying?

GreenFly

When consumers make big purchases, like cars, large appliances or airline tickets, they typically balance many factors. On a flight search website, they might look at cost, departure and arrival times, total duration, layovers, preferred airports and airlines, and so on. For cars and appliances, research has shown that when people can see energy efficiency information while they shop, they are more likely to take energy efficiency into account. Could the same be true of flying? A big difference between cars and air conditioners, on the one hand, and flights on the other, lies in the material benefit consumers receive by choosing energy efficiency. People who buy more efficient air conditioners almost always save money in the long run, via lower electric bills. A nonstop flight, in contrast, will have lower emissions but might also cost more. So would including emissions information on a flight search website really lead travelers to purchase lower-emissions flights? And how should that emission information be presented to best encourage fuel savings?

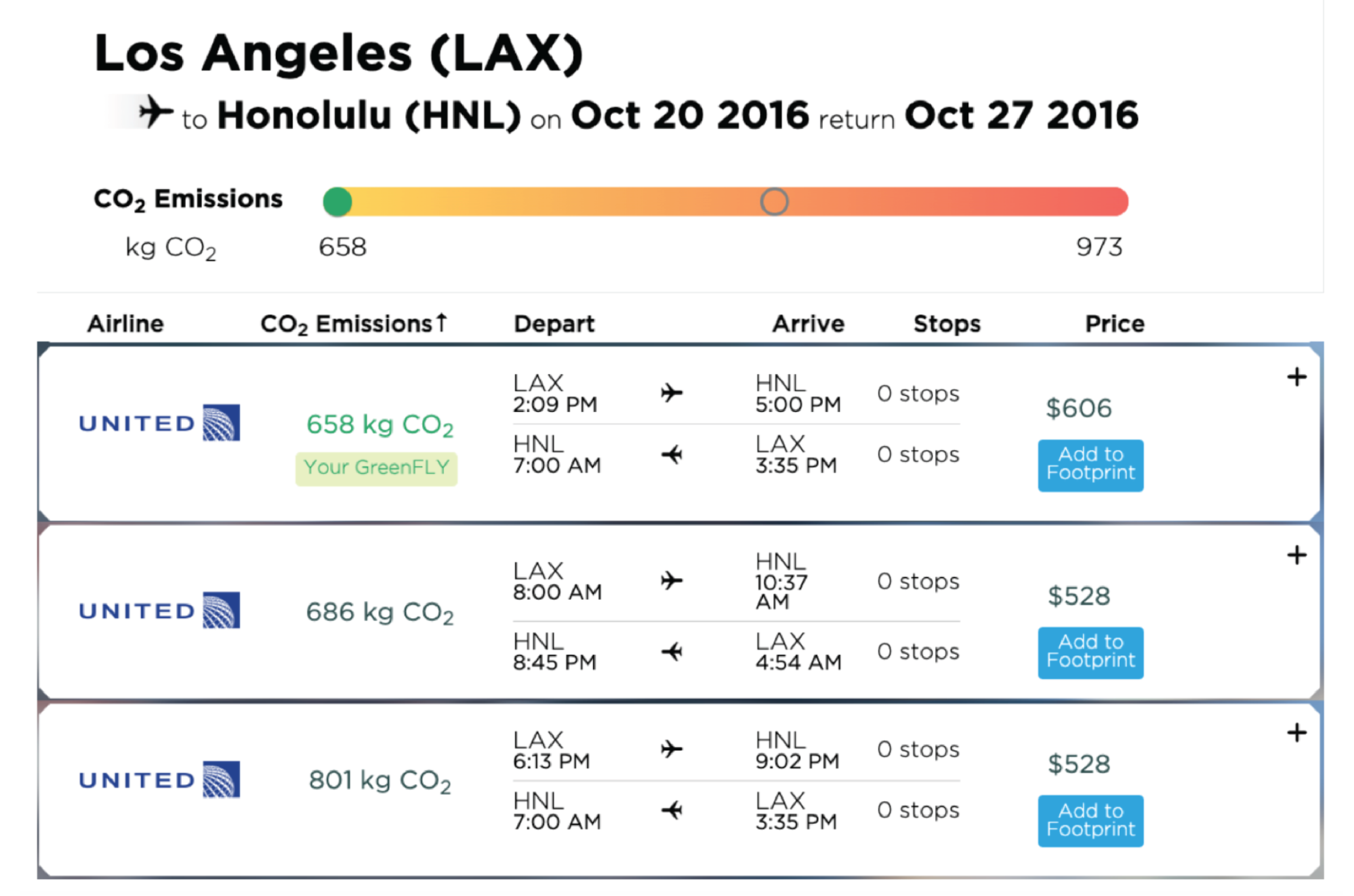

Back in 2014, these questions inspired us to develop a demo flight search website called GreenFLY. GreenFLY presented information to nudge consumers toward lower-emissions flights. In addition to providing the emissions for each flight alternative, GreenFLY sorted flights from lowest to highest emissions, and highlighted the lowest emissions flights, even labeling the lowest emissions flight “Your GreenFLY” (Figure 3). These strategies made emissions information easier to interpret while also highlighting its importance. Translating complex information into labels like these can prime people to make choices (like which flight to take) based on values (like environmentalism) that they might not otherwise be thinking about at the time.

Figure 3. GreenFLY Flight Search Results

At the same time, when making a complex decision, the user wants detailed information. To provide this, we built estimated emissions for GreenFLY based on a methodology published by the International Civil Aviation Organization, based on distance, number of layovers, location of layovers, and aircraft model, and multiplying direct carbon emissions by two to account for other warming effects.

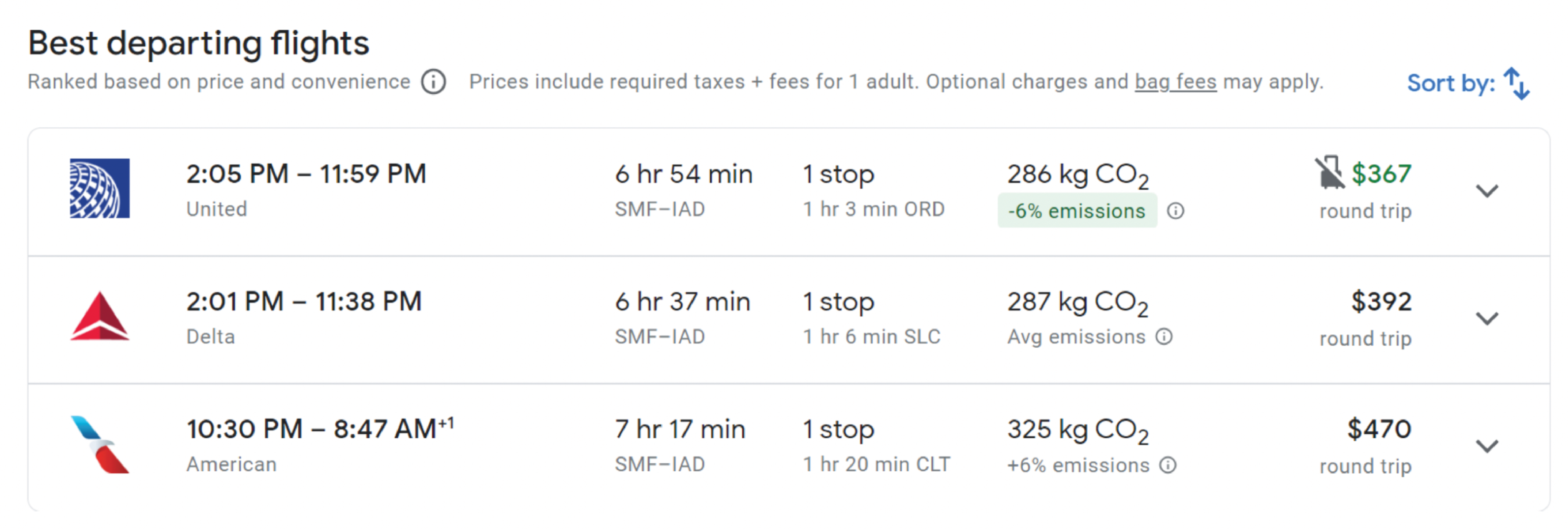

Google Flights estimates emissions in a similar way. Like GreenFLY, Google Flights highlights low-emissions flights with green labels saying, for instance, “-17% emissions” (Figure 4). Google Flights includes a filter to sort by lowest emissions, whereas, in GreenFLY, this was the default presentation. So we think our research using GreenFLY gives some insight into how people are using emissions information in Google Flights.

Figure 4. Google Flights Search Results

Will consumers choose lower-emissions flights?

We conducted two studies to evaluate how these design features affected consumer choices. Our first experiment used a paid online sample of 1,400 people, while the second had a sample of more than 450 UC Davis employees. In both cases, we presented participants with a series of hypothetical scenarios in which they were given two to four flight options, which varied in terms of price, emissions, and number of layovers, and asked to choose one. The emissions estimates for each flight alternative were presented prominently alongside its price, with the lowest-emissions option labeled “greenest flight” (Figure 5). In the first study, participants were asked to assume that the purpose of the flight was the same as their most recent flight, which was generally personal rather than business. In the UC Davis study, flight scenarios (hypothetical destinations) and options (cost, emissions) were developed based on actual employee air travel data for domestic and international university-related business trips. We presented carbon emissions in kilograms in the first study and pounds in the second.

We evaluated the importance participants assigned to different factors by analyzing the choices they made between the flight options. Unsurprisingly, price was the strongest factor determining flight choice, even for the university travelers who reimburse themselves with grant money. However, in both studies, we found that people were willing to pay about $20 more for a flight with 100 kilograms fewer emissions than an alternative offered, even when both flights were nonstop or both included a layover.

This might not sound like a lot, but let’s compare it with the cost of carbon offsets. The flight search tradeoff of $20 per 100 kilograms translates to $200 per ton of CO2 saved, while carbon offsets cost on average $2.50 per ton in 2020. Travelers value the reduced emissions flights at 80 times the rate of traditional carbon offsets.

A good excuse to fly nonstop

Customers already balance cost against other factors when choosing a flight. For instance, it often costs more to fly direct and avoid layovers. Since carbon emissions are lower for nonstop flights, providing emissions information to consumers at the point of purchase might nudge some of them into springing for that nonstop flight. In our first study, we compared flights with layovers and direct flights, and found that our participants would pay $51 on average to avoid a layover without seeing emissions information, but $83 to do so when they see that it is also a lower-emissions flight.

The participants in our second study were our fellow employees at UC Davis, which is closest to the Sacramento airport (SMF), but which is also accessible from the much larger San Francisco International airport (SFO). Nearly half of all U.S. flights occur in such multi-airport regions, and customers have to decide whether to use their closest airport, which may not have many nonstop flights, or to avoid layovers by flying out of the more distant airport. We found that our participants were willing to pay $123 more to fly out of Sacramento instead of San Francisco for a domestic flight, all else being equal. Their willingness to pay to avoid a layover was about the same — $115 — meaning that for many, the choice between a nonstop out of San Francisco versus a layover flight out of Sacramento was indeed a toss-up. But when we highlight carbon emissions, the scale quickly tips toward the SFO nonstop flight — lower emissions break the tie and nudge the user to choose the direct flight.

Of course, how you get to the more distant airport makes a difference, both environmentally and financially. Our emissions estimates assumed that the passenger was driving a reasonably fuel-efficient car and parking at the airport, but taking public transportation at least part of the way (as many of our participants do) makes the greener option even more enticing, while having a friend drive you in a less fuel-efficient vehicle and then return to pick you up can come close to erasing the emissions savings of the more efficient flight.

Because we based our UC Davis experiment on actual employee travel, we were able to model the potential impact of using a GreenFLY-like interface for business travel costs and emissions. We estimated that UC Davis could save 79 tons of emissions, which is about 4% of employee air travel emissions — modest but significant in the context of the University of California system’s recent goal of reducing all travel emissions by 20%. We also found that these relatively modest savings would be combined with an annual $56,000 reduction in airfare costs, mostly due to the increased willingness of travelers to use nonstop flight options out of SFO, which indeed are often cheaper than layover flights from Sacramento. Depending on how employees get to the airport, this financial savings might be negated by higher ground transportation or parking costs. Even so, adding emissions information to flight searches might be a very low-cost way for large institutions to reduce travel emissions.

Airlines are particularly sensitive to demand; they revise their schedules every few months and their prices continuously. If consumers’ lower-emissions flight choices affect profits, it may affect these decisions.

Industrywide actions

The emissions reductions discussed apply to individual or institutional carbon footprints, which only have an indirect effect on airlines’ emissions. If you do not buy a seat on a high-emissions scheduled flight, the airline will try to sell it to someone else, perhaps by lowering the price. The emissions, however, were already “baked in” when the flight was scheduled. Most individual environmental actions function similarly; if you skip a particular hamburger, it has no effect on the cow’s lifetime emissions. That is, the effect of most individual consumer decisions is aggregate: They provide producers with the information that people will buy — and perhaps pay more for — greener options.

Airlines are particularly sensitive to demand; they revise their schedules every few months and their prices continuously. If consumers’ lower-emissions flight choices affect profits, it may affect these decisions. For instance, we might see faster replacement of older “gas guzzler” planes with newer more efficient aircraft, more fuel-efficient upgrades to existing planes, and possibly quicker introduction of electric planes and biofuels. If passengers are more willing to fly coach we might see less first-class seating on new planes. Schedules could also be affected. If lower emissions encourage consumers to pay a bit more for a nonstop from Sacramento to New York, for instance, it might be offered more regularly, and if lower emissions encourage Sacramento travelers to fly out of San Francisco, there might be more San Francisco nonstops and fewer Sacramento layover flights. As an industry leader, Google Flights’ foregrounding emissions information may encourage other travel planning sites to follow suit.

To support this demand, we must also provide improved regional transit access to hub airports that offer many of these lower-emissions flights. This will reduce the inconvenience, cost, and emissions associated with traveling to a less convenient airport for a more efficient (and less expensive) flight.

These changes could have a significant impact, especially on business and institutional carbon footprints, and allow them to meet their emission reduction goals. However, there is always the concern that being able to choose lower-emissions flights will give customers license to fly more. Can more information (for instance, about the overall impact of a flight on a person’s carbon footprint) counteract this effect?

As we work to decarbonize the airline industry and provide low-emission, long-distance travel, providing travelers with the information they need to make environmentally conscious choices can go a long way toward shifting consumer demand, and maybe, shifting the industry.