Millennial Travel: Who Knows About Kids These Days?

Sweeping conclusions about the location and travel desires of millennials may be premature

Millennials have replaced Gen Xers as the generational darlings of the media. From their collective obsession with smartphones and social media, to their perceived tendencies toward tolerance and concern for the environment, to their love of tattoos and avocado toast, millennials are portrayed as distinct in many ways from prior generations. Among the many traits thought to make millennials unique is their travel. They drive less, ride public transit and bicycles more, and have a stronger desire to live in walkable urban communities. Or so the story goes.

But why might their travel be so different? Many pundits have speculated about attitudinal, technological, geographic, economic, and policy explanations for how today’s youth get around. To move beyond speculation, we examined data from the U.S. National Travel Surveys for 1990, 2001, and 2009. We analyzed a wide range of information on travel over time, detailed personal and household characteristics, and spatial information that allowed us to match respondents with the characteristics of their neighborhoods.

Our research examined the determinants of travel for people in their late teens and early 20s, the extent to which their travel differs from that of older adults, and whether youth today travel differently than previous generations.

In a nutshell, we found little evidence of a substantial cultural turn by millennials away from cars and suburbs. We found some evidence of generation-specific declines in driving among millennials, but the effects were modest. So what did have the biggest effect on millennial travel? The economy. Most of the drop in driving was likely due to the effects of the Great Recession.

We also found that millennials were not so unique: Most of the factors influencing youth travel in the 1990s and 2000s similarly affected middle-aged and older adult travel as well. To explain these findings in more detail, we answer eight common questions about millennials and their travel:

Do millennials travel less and rely more on non-driving modes when they do?

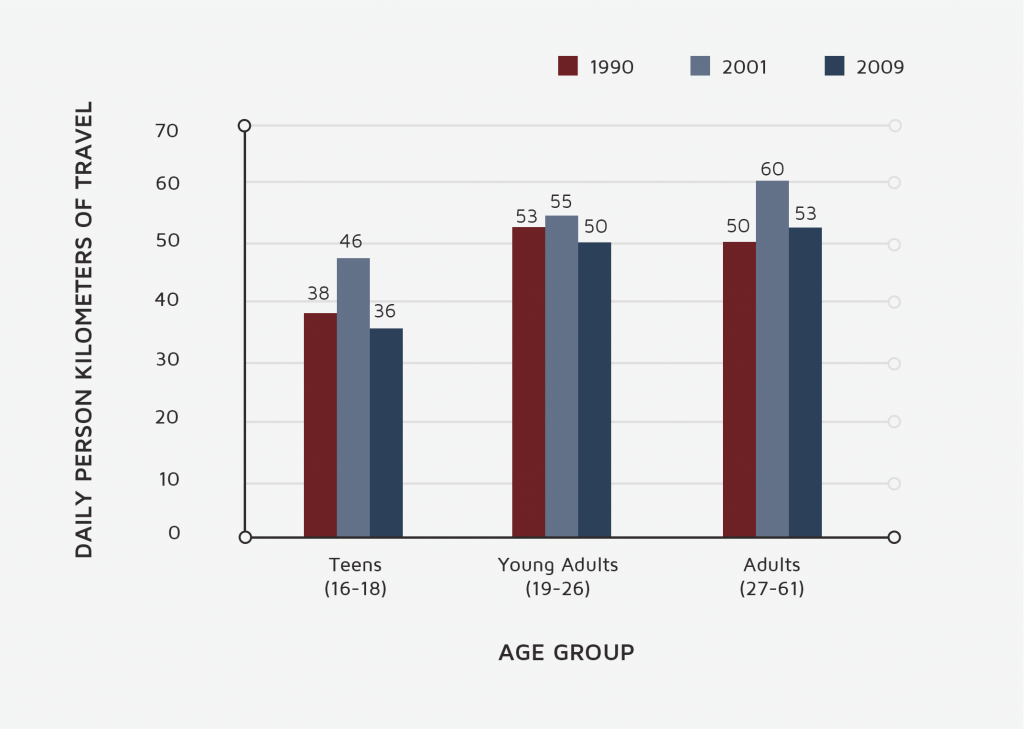

Measured by person kilometers of travel, all age groups traveled less in the 2000s, but this trend was not due to a significant shift from driving to travel by other modes. Average daily travel increased among all age groups during the 1990s (see Figure 1), but had declined by the time the severe economic downturn reached its depths in 2009. The decline was steepest among teens, followed by young adults.

Figure 1. Daily person kilometers of travel by age group and year

While average kilometers of travel rose and then fell during our two-decade study period, we found surprisingly little change in how people travel. Teens and young adults travel by means other than solo driving more than older adults, but the vast majority of all three groups traveled by car throughout the study period, and their likelihood of using other modes remained, by and large, unchanged.

Do millennials travel differently than youth of previous generations?

One theory is that large social and technological changes have fundamentally changed youth and their travel behavior. If this is the case, the travel patterns we see today may be the result of “cohort effects,” traits that groups of similarly situated people continue to share over time. To estimate possible cohort effects, we combined all three surveys and examined the effect of birth decade on travel, taking into account the many other factors that affect travel (including the survey year).

Millennials travel slightly differently than youth did in the past, but not in a way that abandons personal vehicles.

Cohort models provide some evidence for moderate generational effects on travel behavior. All things equal, younger generations appear to travel fewer miles and make fewer trips than previous generations at the same stage in their lives. At the same time, however, younger workers drove alone to work more frequently than similarly aged workers of earlier generations. Millennials travel slightly differently than youth did in the past, but not in a way that abandons personal vehicles.

Do millennials substitute technology for travel?

From the early days of “telecommuting,” planners have speculated that easy access to information and communication technologies would reduce travel, with online communication, entertainment, and shopping replacing trips outside the home. Why travel to see a friend or client, the theory goes, when you can simply FaceTime with them instead?

However, scholars have generally found that these technologies serve as a modest complement to, rather than a substitute for, travel. It may be that being online provides so much information about and access to opportunities that it encourages as many or more new trips than it replaces.

Today’s youth could be a special case. They are the first generation to have never known a world without instantaneous and nearly ubiquitous mobile device access. They also tend to be early adopters of new technologies. Yet despite the staggering increase in mobile device and web access and use, the effects of information and communication technologies on travel (albeit using imperfect measures available in the travel surveys) were small and tended to be associated with more and not less travel.

Do millennials travel less due to increasingly stringent state driver’s licensing regulations?

The short answers are “yes” and “no.” To improve teen driver safety, most states have adopted graduated driver’s license (GDL) regulations that typically include a permit phase with adult supervision, an intermediate phase with restrictions on driving at night and/or with other young passengers, and finally an unrestricted permit phase. Such regulations may restrict teen mobility if they discourage teenagers from becoming drivers or if the nighttime and passenger restrictions limit their travel.

The U.S. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety has developed a point system for ranking GDL programs from low to high levels of stringency, which allowed us to examine states’ uneven transitions from few or no GDL regulations in the early 1990s to universal and mostly strict graduated driver’s licensing by the late 2000s.

Examining the stringency rankings over time, we found lower proportions of teen drivers in states with stricter regulations, as we expected. In 2009, 81 percent of teens in states with the least stringent license requirements were drivers, compared to just 68 percent in states with more stringent requirements. As a result, youth are now more likely to obtain driver’s licenses in their late teens and early 20s, instead of starting to drive as early as they are allowed. While 16- and 17-year-olds now drive less, nearly all youth eventually get driver’s licenses as they age and then travel about as much as similarly situated people from earlier generations. Thus, we find that the overall effect of changes in driver’s licensing regulations on travel was surprisingly small.

Do delayed transitions to adulthood affect millennial travel?

As people age and assume adult responsibilities such as living on their own or having children, their travel tends to increase. But millennials have been taking longer to establish independent lives than youth of previous generations, a trend that accelerated during the Great Recession. For example, young adults struggling to find work increasingly “boomerang” back home to live with parents after having lived independently, in order to take advantage of free or steeply discounted rent, groceries, and car access. Millennials also spend more time in school, contributing to delayed household and employment transitions. These delayed transitions to adulthood may postpone car ownership, and result in fewer work and household-supporting trips and less personal travel.

Our data allowed us to determine whether young adults live with at least one parent. Unfortunately this measure does not directly measure the “boomerang” concept, but we observed a substantial increase in the share of people aged 19 to 26 living with their parents in the 2000s — from 33 percent in 1990 to 58 percent in 2009. The share of 19-to-26-year-olds in school also increased from 14 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2009. But despite these sizeable changes in adulthood transitions, we did not find a statistically significant relationship between youth travel and living with one’s parents or being in school.

Are millennials moving back to the city?

The cultural narrative around millennials casts them as less enamored of the suburban, car-oriented lifestyles their parents favor. Instead of space for kids, a yard, and a two-car garage, the latest generation of young adults is thought to prefer lively cities where they can get around more easily on foot, by bike, and on public transit.

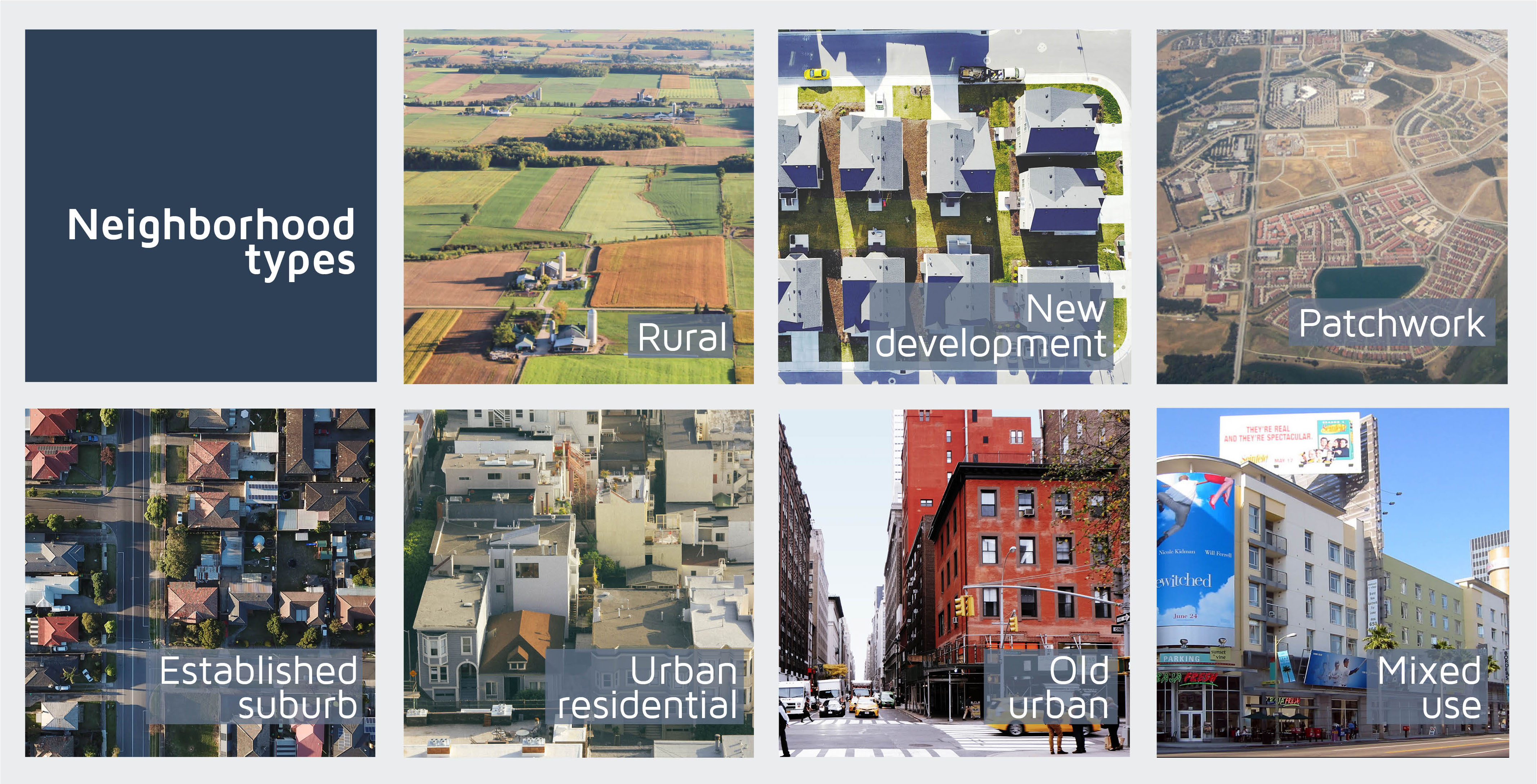

Indeed, data show that millennials are more likely to live in dense, walkable urban areas than older adults. To test this, we classified the characteristics of the built environment and transportation infrastructure of nearly all U.S. neighborhoods into one of seven types:

While a higher percentage of youth than adults live in neighborhoods that tend to be found in cities — Urban Residential, Old Urban, and Mixed Use — more than half of all youth live in the three suburban neighborhood types, suggesting that the suburbs are far from dead to millennials. Travel differences across the seven neighborhood types are surprisingly small, with one exception.

Residents in dense, transit-rich Old Urban neighborhoods tend to travel very differently: they make fewer trips, travel fewer miles, have lower rates of automobile ownership and licensing, are less likely to drive alone, and are much more likely to walk and take transit than are the residents of any other neighborhood type. The catch is that very few places are this dense and transit rich. Old Urban neighborhoods account for just 4 percent of U.S. neighborhoods, the vast majority of which are found in New York, Los Angeles, and a few other very large cities. Just 6 percent of all Americans aged 20 to 34 live in Old Urban neighborhoods.

Any “back-to-the-city” movement was dwarfed by what might best be described as a much larger “out-to-the-suburbs” movement.

Besides the relatively small number of Old Urban neighborhoods, residential location has played only a small role in recent changes in millennial travel. Nor has there been much change in the percentage of youth living in urban areas over time. During the 2000s, the number of millennials living in urban neighborhoods increased by more than four million, yet any “back-to-the-city” movement was dwarfed by what might best be described as a much larger “out-to-the-suburbs” movement. The increase in the number of youth living in sprawling New Development suburbs was more than 50 percent greater than the increase in the youth population in all six other neighborhood types combined.

Can the economy explain the decline in millennial travel?

Today’s teens and young adults came of age amidst the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. Between 2001 and 2009 youth unemployment more than doubled, from 4.2 to 9.3 percent. We found a strong and consistent positive relationship between employment and youth travel, which suggests that high youth unemployment rates were central to the decline in youth travel in the 2000s.

However, the economic downturn appears to have had an even larger effect on adult travel. The relationship between employment and personal travel was 32 percent greater among adults aged 27 to 61 than for those aged 20 to 26. Older working adults averaged 7.4 kilometers more per day than non-working adults, compared to 5.6 kilometers more for employed young adults. So while the economy clearly influenced millennial travel in the 2000s, it affected the travel of all working-age adults, not just youth.

So what was behind the decline in millennial travel in the 2000s, and what lessons can we draw?

After controlling for personal, household, locational, and travel factors, the effects of societal trends on personal travel are surprisingly muted — with the notable exception of employment. Many of the factors popularly associated with millennials are not unique to that generation; they appear to have a similar or, in some cases, even greater influence on the travel of older adults. Finally, for youth in particular, personal travel in 2009 was not significantly different from 1990. The outlier in our sample may have been 2001, a time when unemployment was near a historic low of 4.2 percent and personal travel was near an all-time high.

Some observers have used the recent dip in youth travel to argue that transportation investments should be refashioned to better support millennials in their desire for more urban, less car-centric lifestyles. However, our analysis shows that such sweeping conclusions about the location and travel desires of millennials may be premature and are surely too simplistic. Our findings suggest that the future of travel — for youth as well as adults — largely hinges on the state of the economy.

Data on U.S. vehicle kilometers traveled in the 2010s support this conclusion. As the economy has rebounded from the Great Recession, so too has vehicle travel, which is now at a historic high. Analysis of data from the recently-released 2017 National Household Travel Survey will shed some additional light on post-recession trends. In the meantime, while policy shifts away from cars are likely justified on the basis of both economic efficiency and environmental sustainability, there is little evidence that car travel is going the way of the print newspaper thanks to the shifting preferences of millennials.