Why scooters are the future of transportation

Almost overnight, electric scooters, e-bikes, and dockless bicycles have become a fixture in cities across the United States and beyond. While these devices might seem like toys, or annoyances, or possibly safety hazards, my decades of research and teaching on transportation planning leads me a different conclusion: Light-duty, sustainable mobility should be a central part of our transportation future.

The reason is simple: Most trips are short, but we usually drive because no other technology can rival the convenience of the car even for trips of one to two miles — until now.

Nationally, half of all trips are less than three miles. In cities, that fraction can be higher. We often don’t need two tons of steel with a couple of hundred horsepower to go three miles or less, but we drive because other options are not nearly as convenient. What would happen if we could move those short trips to technologies that are smaller and more environmentally friendly?

Some insight comes from a study that I completed with colleagues Genevieve Giuliano at USC and Yuting Hou and Eun Jin Shin (now at Singapore University of Technology and Design and Yale-NUS College, respectively.) With funding from the USC Sol Price Center for Social Innovation, we compared job access for commuters using transit versus those driving to work in San Diego. Several results point to the potential advantages of technologies like scooters and bicycles that can bridge the gap between home, jobs, and transit stations.

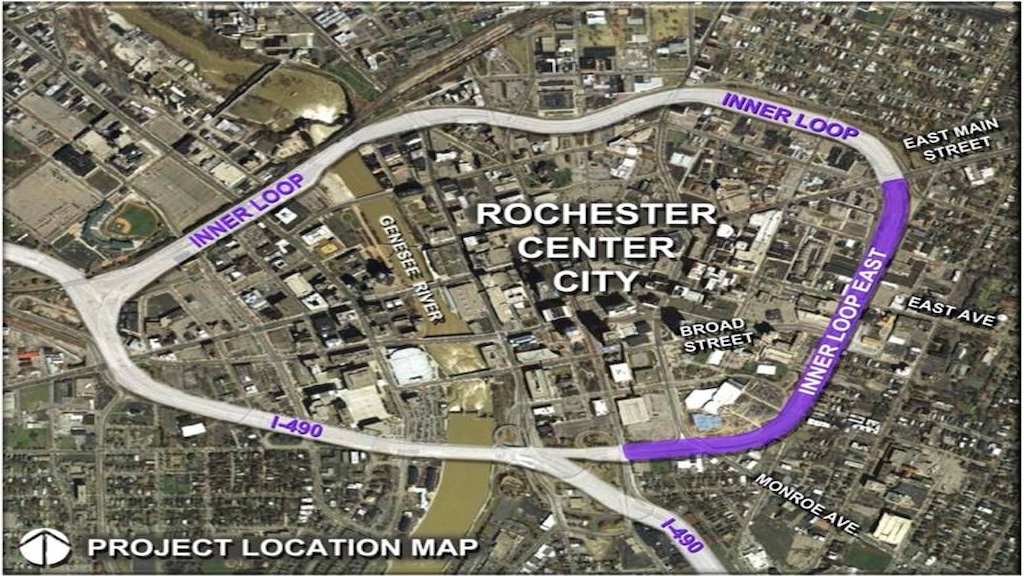

A typical car commuter in San Diego’s poorest neighborhoods, when driving for 30 minutes, can reach 30 to 40 times more jobs than a person who starts in those same neighborhoods and commutes 30 minutes by transit. Why is there such a large difference between car and transit job access? The reasons are familiar to transit riders everywhere — transit commuters must walk to and from stations, wait for the bus or train, and often transfer, while cars go point-to-point.

Just getting to and from transit stations, for typical San Diego commuters, was almost 20 percent of total transit commute time. We studied what would happen if we could move people to and from stations on bicycles.

Our results showed that, in San Diego, if people could bike at both ends of a transit trip, to and from stations, the improvement in job access would be larger than what we could get by increasing the number of buses and trains by 50 percent citywide. However, adding more buses and trains is expensive. Moving persons back and forth to stations at bicycle speeds could be cheap — but how do we do that given that many persons may not want to or be able to bike?

Enter the e-mobility revolution. For the first time, we have the possibility of new technologies that can replace short car trips. Scooters and dockless bikes are likely the first of many light-duty, sustainable, short-trip vehicles. These technologies hold the promise of replacing short driving trips with something smaller, lighter, and much more environmentally friendly.

Of course there are issues that must be addressed. Scooters and dockless bikeshare can create clutter, interfere with pedestrians, and pose safety issues. Cities need to regulate this new mobility. In thinking about how to do that, cities should remember these principles:

- When e-mobility uses public space, users or the mobility companies should pay the public for the use of that space. These devices use sidewalks, streets, and bike lanes, and it makes sense to charge reasonable fees for the use of that space.

- We should do all we can to foster competition. Limiting the number of firms that operate might seem a sensible way to reduce scooter or bike clutter or to license the best-behaving firms. But picking winners, or even the number of winners, is unwise. It is better to let the market choose the number of companies that can profitably operate. Clutter can be managed by carefully designating parking locations for scooters and dockless bikes — maybe by replacing a car parking space on, for example, each block with scooter and bike parking.

- Rather than requiring scooter and bicycle riders to wear helmets, we should aim to build infrastructure that makes our streets safe for all users. The same infrastructure that fosters safety for new e-mobility (i.e. slowing car travel speeds) will make our streets safer for pedestrians.

- In the information age, data are valuable. These new mobility companies are generating large amounts of data on when, where, and how people travel. Cities should require data sharing as part of any license to operate.

The best thing planners and policymakers can do now is to realize that e-scooters and shared bikes are the harbingers of low-impact transport solutions that have the potential to solve vexing problems. We should regulate this industry, but in ways that focus on compensating the public for the use of public space and making streets safe for everyone in and out of cars, all while sharing data and fostering as much competition as we can. The cities that best do that will be leaders in this new transportation era.

Note: This piece was also recently published on the Social Innovation Blog of the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy.

These recommendations seem totally sensible. One thing I would add would be penalties for bad actors. I’ve seen electric scooters racing down sidewalks with pedestrians jumping out of the way and also riding the wrong way in traffic on the roads. I don’t know if the technology is there to detect this behavior and perhaps ban such riders for 30-90 days.