Optimal Pricing of Public Parking Garages

Cities can better manage off-street parking by prioritizing occupancy and availability, not just revenue

Cities are coming around to the idea that on-street parking should be managed and priced based on the demand for the space. San Francisco, for example, created SFpark, a program that adjusts the prices of 7,000 parking meters to achieve a target occupancy rate for on-street spaces, and received much praise among transportation policymakers and professionals.

Yet as on-street parking management programs garner attention, cities routinely build off-street parking garages at great cost with scant public scrutiny. Other than recovering the cost of building and maintaining the garages, cities commonly fail to set clear goals for managing their off-street parking supply. This is not the case, however, in San Francisco, where SFpark also implements demand-based pricing for public parking garages. The program has experimented with adjusting the prices of 11,500 off-street parking spaces in 14 city-owned parking garages, and is a model for pricing public garages to improve parking efficiency and reduce traffic.

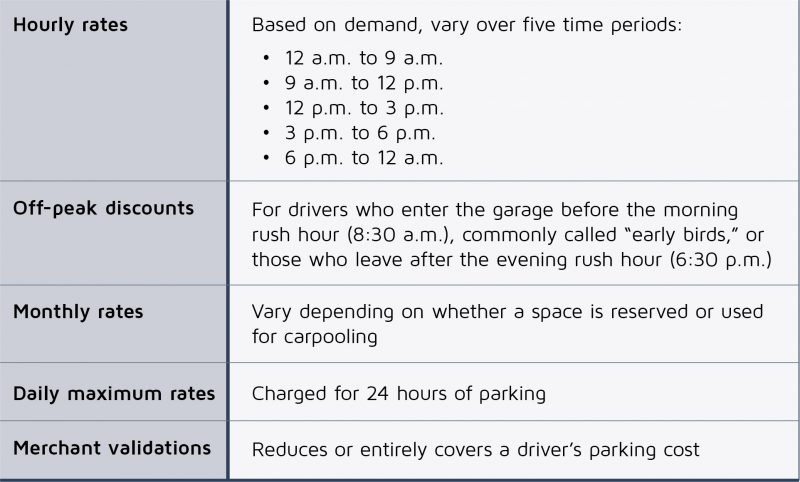

Effective parking management presents a challenge. Like airline seats and hotel rooms, parking spaces are perishable goods that cannot be stored and are wasted if they are not used. Effective management of a perishable good has two essential components. First, the wasted time when an airline seat, hotel room, or parking space goes unused cannot be resold later. Second, perishable goods are optimally managed by charging different prices at different times or for different people. In the private parking industry, price differentiation is already common practice as shown by the lower hourly rates offered to early birds or by validated parking for nearby shop customers.

Cities should treat their public garages like hotels for cars, and parking prices should resemble hotel prices that vary based on demand.

Cities should treat their public garages like hotels for cars, and parking prices should resemble hotel prices that vary based on demand. Hotel prices vary according to the size of rooms, the day of the week, the season, and other factors, and so can parking prices. Hotels that operated without variable prices would quickly generate the same kinds of complaints often heard about parking.

Effective parking management requires reasonable revenue goals. For off-street parking, cities commonly set revenue goals based on the cost to build and operate garages. A 2014 study in 12 U.S. cities found that construction costs averaged $24,000 per space for aboveground parking structures and $34,000 per space for underground garages. Low parking prices may not recoup construction costs and can lead to a financial loss, but prices high enough to recoup construction costs can leave substantial vacancies.

In public garages, cities must also balance the competing goals of reliable availability and high occupancy. Low occupancy means parking spaces are readily available, but the garage brings few visitors to adjacent businesses, schools, and other amenities. High occupancy means the lot maximizes parking space use but may deny service to new customers. The greater the variation in demand during a time period, the more difficult it is to balance the two goals. In order to achieve a balance, a driver’s probability of finding an open space upon arrival is a key guide to setting prices

A city should have three goals when setting garage occupancy targets:

- Ready availability

- High occupancy

- Revenue

By relying on a single target, such as revenue, cities leave the other two goals unfulfilled. No evidence suggests the weight that cities should assign to each of these goals, but local policymakers should manage their parking garages based on explicit concern for all three.

SFpark’s innovations in off-street space management

Unlike most other cities, San Francisco controls a substantial portion of its off-street parking supply. City-managed garages account for about 60 percent of the publicly available off-street parking spaces in some neighborhoods, and about 16 percent of the city’s total off-street supply.

Before SFpark, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) set parking prices in garages to cover costs rather than to manage occupancy, and charged drivers more to park off-street than on-street. This pricing system encouraged drivers to circle blocks hoping to find a free or cheap on-street space, rather than park off-street. On-street metered parking was usually scarce, while garages had many available spaces most of the time.

SFpark adjusts off-street parking prices every three months based on the parking demand at each garage during five different daily time intervals. The city aims for each garage to have an average occupancy no lower than 40 percent and no higher than 80 percent. If expected garage occupancy exceeds 80 percent for a particular time period, SFMTA raises the hourly rate for that time period by $0.50. If garage occupancy is below 40 percent during a time period, the hourly rate is lowered by $0.50 for the subsequent quarter. SFpark’s rate-setting policies for both on- and off-street parking have brought garage hourly rates equal to — or in many cases below — nearby parking meter rates, giving drivers a financial incentive to go straight to the garages rather than cruise for on-street parking.

In addition to varying hourly prices based on demand, SFpark’s garage policy also addresses non-price factors. For instance, rush-hour queues at garage entrances and exits cause drivers to lose time. In response, SFpark offers off-peak discounts for drivers who arrive before the morning peak or depart after the evening peak to lessen the congestion in and near garages at rush hour. As a result, fewer cars now enter during the morning rush and exit during the evening rush.

SFpark has not, however, simplified the hourly rates for parking prices. Pricing based on the time of day and on the level of demand has actually made hourly rates more complicated. The hourly price, and thus the total parking charge, now depends on when the drivers arrive, not simply on how long they stay. Drivers may also pay at multiple rates depending on when they park. For instance, a driver might pay a daytime hourly rate for the first portion of a parking session, and a lower evening rate for the remainder of the stay.

Varied parking rates, price maximums, discounts, and validations make calculating drivers’ responses to price changes difficult. Parkers each pay different prices and no one price fully describes how much any particular driver might pay.

Table 1. SFpark off-street parking rate variations

SFpark results: Price, occupancy, and revenue

Similar to findings for on-street parking under SFpark, hourly parking prices in individual garages varied widely in response to local demand. Planners will never be able to accurately predict the prices needed to achieve the target occupancy for every garage at every time period. Instead, the best way to achieve a target occupancy goal is to continue what SFpark already does: adjust prices in response to the observed occupancy based on trial and error. Because most garages initially had many vacant spaces on most days and at most times, the average hourly price of parking across all garages fell by 20 percent during the program’s first year. During the program’s second year, the average daytime hourly prices at SFpark garages rose, but still remained lower than the average price before the program started.

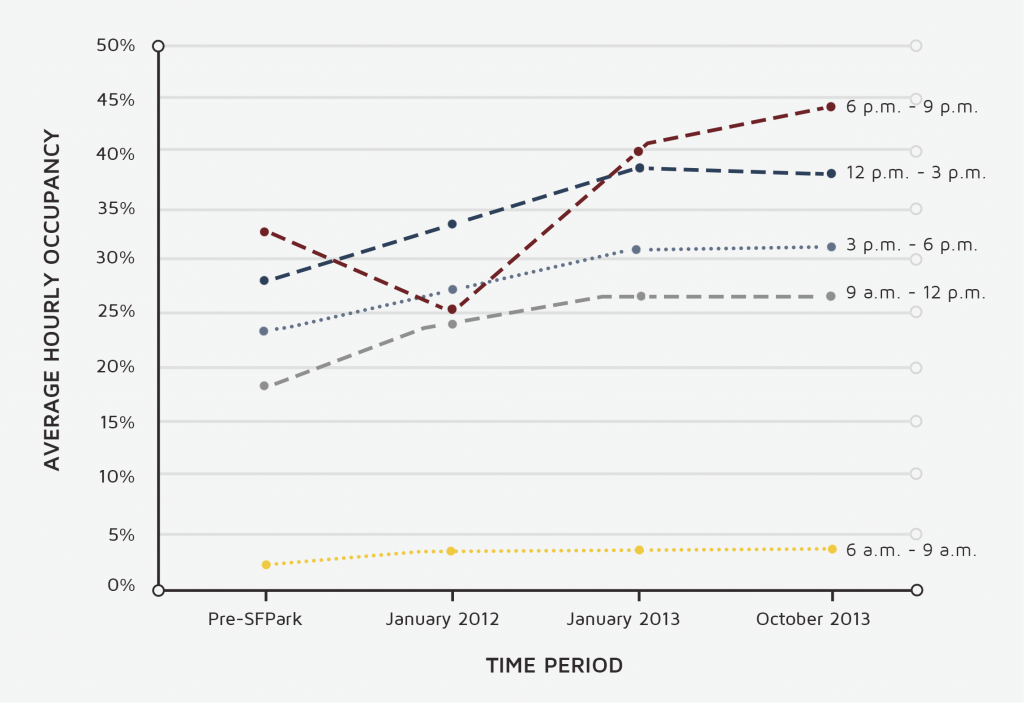

While prices fell modestly, average weekday occupancy for hourly parkers rose by 38 percent in the first two years of the program. As Figure 1 shows, this positive trend remained remarkably consistent across normal working hours, with more erratic responses during the early morning and late evening periods.

Figure 1. Average hourly occupancy in SFpark garages

The SFpark program presented a large revenue risk for the SFMTA. Total revenue across garages dipped at the outset of the program, but recovered and surpassed pre-program revenue by the end of fiscal year 2013. By comparison, revenue from the municipal garages outside the pilot program remained steady throughout the period. In the end, the SFMTA’s experiment clearly paid off.

After the SFMTA’s first two years of dynamic pricing in municipal garages, drivers paid lower hourly prices. Not surprisingly, drivers facing lower prices are more eager to park in garages, leading to higher occupancy. As a result, San Francisco has slightly increased its revenue yield from the garages with demand-responsive pricing. In other words, everyone wins under SFpark. Focusing on the combination of lower prices, higher occupancy, and more revenue, rather than just one of these goals, benefits drivers, businesses, and the city.

Focusing on the combination of lower prices, higher occupancy, and more revenue, rather than just one of these goals, benefits drivers, businesses, and the city.

SFpark’s positive effects are best illustrated by looking more closely at the Performing Arts Garage, which is located downtown near the Civic Center neighborhood. Before the SFpark program, garage daytime rates were set uniformly at $2.50 per hour, and peak weekday hourly occupancy averaged only about 25 percent. Under SFpark, low occupancy rates resulted in repeated hourly price reductions every three months. By January 2013, hourly rates for the Performing Arts Center had dropped to the statutory minimum of $1 per hour. As prices dropped, the garage’s peak weekday occupancy rose to about 85 percent and total revenue increased more than 10 percent.

Improving SFpark’s off-street program

Despite SFpark’s success in improving off-street parking management, the program can make several further improvements. Garage prices are not reduced unless occupancy falls below 40 percent and are not increased unless occupancy rises above 80 percent. The SFMTA reasons that maintaining such a wide range will help to avoid peak occupancy above 95 percent. But since peak occupancy rarely, if ever, exceeds 95 percent in any garage, SFpark should set the minimum target range at 60 percent occupancy or higher to optimize use.

Price changes should also be more transparent. SFpark maintains explicit criteria for adjusting prices based on observed occupancy, but in practice, it does not always follow these guidelines when there is political resistance to price increases. Refraining from rule-based price changes distorts the off-street parking market and invites criticism from skeptics. The SFMTA should, at a minimum, publicly explain its rationale if it sets prices to achieve alternative objectives.

The principles of performance-based pricing for municipal garages can also be applied to parking assets managed by other public entities. For instance, universities located in dense urban areas often maintain parking lots and garages on their campuses. These spaces are occupied during the day primarily by those with permits, and many remain vacant in the evening. Reducing the price of parking in the evening to increase occupancy of the garages can increase attendance at cultural events, improve the sense of community, enhance safety by filling otherwise dark and empty garages, and relieve parking congestion on nearby residential streets.

SFpark reduced parking prices in the municipal garages, increased garage occupancy, and increased parking revenue. The program’s results show that cities can more effectively manage their parking assets to maximize public benefits by setting occupancy, rather than revenue, targets. Thus, small changes to management practices can produce large benefits for cities.