Do more EVs mean less transportation funding? Not so, says new study

California is in the midst of several ambitious shifts in its transportation infrastructure, funding, and vehicle fleet composition.

In 2017, SB 1 created new funding mechanisms, primarily through a schedule of increases to the gas tax, to support new infrastructure across the state. At the same time, the state is also committed to an air quality and emissions goal former Gov. Jerry Brown established in 2018: reaching a total of 5 million zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) by 2030. Such a rapid increase of electric cars would mean fewer drivers paying fuel taxes, the state’s largest source of transportation revenue.

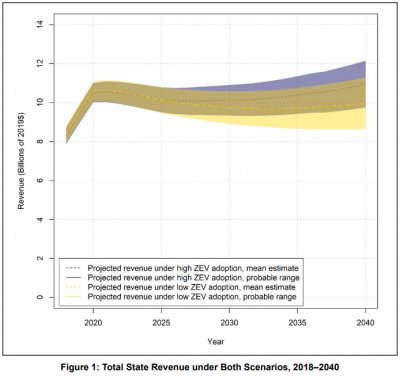

A new study by Martin Wachs, Hannah King, and Asha Weinstein Agrawal examined the impact on California revenue over the next 20 years across two ZEV adoption scenarios. Surprisingly, it finds that an accelerated adoption of ZEVs would generate $2 billion more annually by 2040 than a slower adoption rate.

A follow-up to a 2018 report, The Impact of ZEV Adoption on California Transportation Revenue examines how the scenarios would affect six key revenue sources that specifically fund transportation projects.

In the first scenario, California drivers adopt new ZEVs at the current rate of about 26,000 cars per year. The second posits a much more rapid rate of adoption needed for California to reach its goal of 5 million total electric vehicles by 2030.

SB 1 legislation created two mechanisms through which ZEVs would generate transportation funding revenue — apart from fuel taxes. Transportation Impact Fees (TIF) are an annual fee all vehicle owners pay, which range from $25 to $175 depending on the vehicle’s value. Electric vehicles are likely to have high dollar values and that means they generate more fee revenue than the cars they replace. The Road Improvement Fee (RIF), which begins in July 2020, is a separate annual fee of $100 charged to ZEV owners to compensate for the revenue from fuel taxes that they do not pay.

The authors found that under both scenarios, the revenue from fuel taxes did fall as expected. However, the higher value of more, new electric vehicles means that revenue from TIFs grew in both scenarios, and by more in the rapid-adoption one. For both scenarios, the total annual revenues increase rapidly at the same amount until the early 2020s, but then begin to diverge. The rapid-adoption scenario ultimately has the higher annual revenue, of about $11 billion, in 2040.

The chart below illustrates these trends, providing mean estimates and possible ranges of revenue for each scenario.

The authors caution that diversions from their key assumptions could change how much revenue the state collects under the high-adoption scenario. If the average price of new electric cars fell more quickly than expected, for example, their value would be lower and so would their TIF rate, dropping the study’s projected revenues. Drops in population growth would also have a similar effect. But in the short run, as the state looks to shift drivers from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles, the new fee structures means it can effectively make up for the loss in gas tax revenue while meeting fleet emissions goals.

Interested in writing for The Circulator? Submit a post.