Spreading the Gospel of Induced Demand

Induced demand is commonly misunderstood, and planners need to help.

Share

Transportation scholars have long known that we cannot build our way out of traffic congestion. Adding new road capacity attracts more travelers from other modes, other times of day, and other routes. In other words, “If you build it, they will come.” Perhaps surprisingly, adding new transit capacity does the same thing. A driver who leaves a busy rush hour freeway to ride a train will soon be replaced by someone else. This phenomenon is known as induced demand, and it is not a new idea. Careful observers noticed cases of induced demand over 100 years ago, and Anthony Downs wrote his classic treatise on the persistence of peak-hour traffic congestion more than 50 years ago. More recently, academics have carefully documented and measured induced demand in a variety of contexts.

Despite decades of evidence about induced demand, governments continue to widen roads, promising that the extra lanes will relieve congestion. Departments of Transportation rarely consider induced demand during environmental review. As a result, we spend billions of dollars each year on road-widening projects that ultimately provide little of the relief they promise. Less often, but still all too frequently, the same promises are used to construct rail lines with similar outcomes for traffic congestion.

We argue that part — though certainly not all — of the problem is that the public largely misunderstands induced demand. Given this misunderstanding, transportation planners, engineers, and other practitioners must become evangelical about induced demand. They should spread the gospel that widening roadways to mitigate congestion is almost certain to fail, and that building new transit to fight congestion will likewise be disappointing. We hope a greater public understanding of induced demand will help reorient transportation investments away from the idea that construction solves congestion.

Planners should spread the gospel that widening roadways to mitigate congestion is almost certain to fail, and that building new transit to fight congestion will likewise be disappointing.

In making our call for evangelism, we draw on several of our recent studies about Americans’ views about transportation planning. Our goal with this project was to understand Americans’ transportation policy preferences and explore how people’s knowledge and foundational beliefs inform those preferences. We surveyed a representative sample of 597 Americans and asked them 49 questions about transportation. We focus here on one question about knowledge (do respondents understand that widening a roadway is unlikely to provide permanent congestion relief) and three questions about policy preferences (what should be the overall goals of transportation policy, how much do they support three different congestion-relief options, and which of the three do they prefer). We also tested whether learning about induced demand could shift preferences and whether those newly shifted preferences held or reverted to baseline after six months.

In addition, we surveyed 520 university students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate transportation courses in the United States who filled out an abridged survey. We did so because we wanted to understand the preferences and views of future engineers and planners.

Below, we summarize our key findings and make three calls to action.

Finding #1: Most Americans don’t understand that we can’t build our way out of congestion, in contrast to planning and engineering students

We asked respondents if adding lanes to a roadway is “likely” or “unlikely” to reduce congestion in the long term. We use this question as a simplified assessment of whether they understand induced demand. We emphasize road widening because it is common. Relatively few Americans live in places where the government has built rail, but most live in places where it has widened a road.

Most respondents got this question wrong: Sixty-four percent of the general public said that adding a new lane is likely to reduce congestion in the long term.

In many ways, the widespread misunderstanding of roadway expansion’s short-lived benefits is unsurprising; induced demand is counterintuitive. Moreover, promises that road widening will ease congestion have formed the backbone of U.S. transportation policy for decades and continue to motivate project selection today. The public has likely heard, read, and seen promises of congestion relief from politicians, policymakers, and even transportation planners for local road construction projects.

Surveying the transportation students yielded a different result. Nearly all planning students (93%) knew that adding lanes is unlikely to reduce congestion in the long run; 58% of engineering students said the same, which is less than the planning students but far more than the general public (36%). Due to their specialized training, we expected students to have a greater understanding of this concept than the public, but we were somewhat surprised that engineering students were much less knowledgeable about this topic than planning students. We are exploring the cause of these differences in ongoing work.

Finding #2: Knowledge is closely associated with transportation preferences, but almost no one understands induced demand

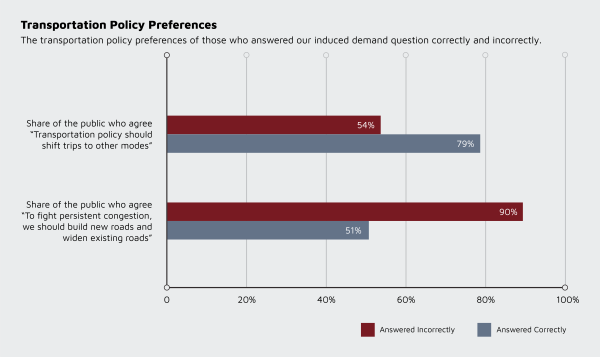

Knowledge about induced demand matters because individuals’ understanding of this topic is correlated with policy preferences. First, consider respondents’ views on the overarching goals of transportation policy. We asked whether “Transportation policy should…” (1) “make it easier for most people to drive for most trips,” or (2) “try to shift more trips toward public transit, walking, and bicycling.” The former reflects the status quo, while the latter represents a new direction for transportation policy. Respondents who understood that road expansion will not alleviate traffic congestion were more supportive of shifting trips to other modes than those who misunderstood it (79% vs. 54%).

Next, we asked respondents what they thought should be done about traffic congestion. We asked this question in two different ways. First, we assessed their level of support for three different policies to address persistent congestion: build and widen roads, invest more in public transit, and implement congestion pricing. We then asked them to pick their preferred option among the three.

Unsurprisingly, respondents who believed road widening would likely reduce congestion in the long term overwhelmingly preferred to expand roadways (90% of this group favored road expansion). This widespread support makes sense since these respondents believe congestion relief will last. But what should we make of the 51% of respondents who still supported road widening despite answering our induced demand question correctly? Some respondents might still support road widening even if they think congestion relief will be short-lived, perhaps because they like the idea of the roads holding more people, even if their speed is still slow. Alternatively, this group might believe nothing can solve congestion but that building roads delivers local construction jobs, which they value. Lastly, we may also be overestimating the public’s understanding; the survey question about induced demand had only two choices, so anyone who just guessed had a 50 percent chance of being right.

Figure 1. Knowledge and transport policy views

Now let’s consider the other two options for fighting congestion: building transit and using pricing. If respondents truly understood induced demand, they would know that only congestion pricing can provide long-lasting congestion relief. But among those who answered our induced demand question about the roads correctly, only 7% selected pricing as their preferred option. In a separate question, just 29% expressed support for the idea.

What this group overwhelmingly supported, instead, was improving transit to address persistent congestion. Among those who knew that expanding roadways was unlikely to address persistent traffic congestion, 89% supported improving transit to fight persistent traffic congestion and 73% selected it as their preferred option. Support for transit was similar among planning students, nearly all of whom correctly answered our question about roadway induced demand.

In short, our evidence suggests that almost everyone who answered the induced demand question accurately didn’t really understand induced demand.

What’s going on here? Some people, again, may have just had a lucky guess on the roadway induced demand question, and their subsequent answers reveal their lack of knowledge. Some respondents might understand that induced demand will erode any congestion relief from transit, but nevertheless think transit improvements are the best way to fight congestion (high-quality transit can let people avoid congestion, even if it can’t reduce it). For that matter, some people might understand that only pricing works, but worry that road tolls are unfair.

Another possible explanation: People have an easier time understanding concepts when those concepts reinforce, rather than contradict, their existing preferences and beliefs. People who like transit and dislike driving might readily understand induced demand when it is applied to roads, but have a harder time grasping it when it comes to transit (a difficulty that conveniently reinforces their existing preferences). Similarly, respondents may be applying a mental heuristic that is not uncommon with survey questions, which is to swap an easy question for a hard one. We asked people to assess three approaches “to address persistent congestion…”, which is a question that requires some thought and technical knowledge. Some respondents may have used a mental shortcut and, without noticing, substituted in an easier question, along the lines of “What do you prefer…” or “What do you think transportation policy should do?” When this occurs, respondents end up telling us which policies they like, rather than carefully reflecting on which policies work.

Some combination of selective understanding and mental heuristics would help explain why almost all the planning students chose transit to fight congestion. If pressed, we suspect (and hope!) that at least some of these students would correctly note that only dynamic pricing could eliminate congestion in the long term (just 32% of the public, and 55% of the planning students, support using pricing at all).

Finding #3: Educational efforts can shift views, but one-time messaging is insufficient

Given that most people misunderstand induced demand, we wanted to know whether better information could correct these misperceptions. To find out, we included a “refutation text” in our survey of the public. After these respondents completed the first part of the survey, they read a short passage explaining the basics of induced demand:

Many people think that adding lanes to the highway will ease congestion for years to come. In reality, research shows that the congestion relief is short-lived.

Before the new lanes, some drivers avoided the congested roadway by driving on different routes, driving at different times of day, or walking, biking, or riding transit instead. Immediately after the new lanes are added, drivers can travel at higher speeds. The faster speeds attract drivers who previously avoided the area due to congestion. Soon, the roadway is just as congested as it was before.

In sum, adding lanes to a congested roadway allows more drivers to travel when and where they would like to go, but does not eliminate traffic jams.

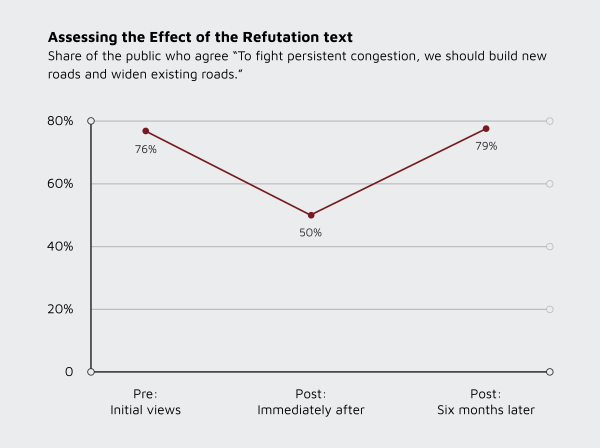

The next question after this refutation text asked respondents again about their support for building roads. Immediately after reading the refutation text, support for expanding highways dropped significantly among the public, from 76% to 50%.

That was encouraging, but six months later, we reached out to the same respondents to examine the longer-term effects of the information. Over 400 of the original 597 respondents completed a follow-up survey. We found that support for road widening had rebounded to initial levels (79% compared with 76% originally). What happened? Possibly some of the original drop in support was a product of “acquiescence bias”: a tendency for survey respondents to try to “get the right answer” rather than of their understanding changing. Assuming the refutation did change some people’s minds, however, the rebound suggests that while educational efforts may be effective in the short term, a single message is unlikely to move the needle permanently.

Figure 2. Respondents’ preferred policy response across three time periods

Calls to action

Based on these key findings, we offer three calls to action.

Call to action #1: Stop justifying roadway and transit projects with the promise of congestion relief

Congestion relief has been the raison d’être for roadway expansion projects for over 100 years. While it may be tempting to market road widening as congestion relief — congestion relief is, after all, politically popular — relying on it to justify investments will do little to encourage transportation policy reform and is likely to frustrate the public. Even worse, repeatedly crying wolf on congestion relief has the potential to erode public support for transportation spending.

The same logic extends to justifying transit projects; while the public currently seems willing to swallow the congestion-relief promises of transit promoters, they may eventually tire of doing so. Even if they don’t, no one is helped when we design transit to do something it can’t. Moving away from a congestion-relief justification for transit prevents us from squandering limited transit resources trying to make cars move faster and lets us prioritize different projects that make better use of public transportation’s potential.

Call to action #2: Spread the word about induced demand

Transportation planners, scholars, and activists should become evangelical about induced demand. Most of the American public is misinformed about induced demand — even when people appear to understand the futility of building roads to fight congestion, many seem to misunderstand the broader concept, given support levels for transit as a solution. We must work to correct that misunderstanding. As we have shown, simply explaining the fallacy of highway expansion to relieve traffic congestion is an effective strategy, but only in the short term. Thanks to the vagaries of memory or desirability bias, people end up returning to their original preferences.

What will it take to shift perceptions permanently? We suggest repeated messaging via a variety of formats. These formats could include print media like op-eds and policy briefs, new tools like the recently developed induced demand calculator, social media campaigns, or more creative outlets — like documentaries or museum exhibits on the detrimental legacy of highway expansion. As any good storyteller knows, it is important to appeal to more than just someone’s logic and speak to their heart. Including personal stories and anecdotes may help elevate the pathos (appeals to emotions and values) to complement the elements of logos (appeals to logic and reason) and ethos (appeals to credibility and trust).

Shifting perceptions permanently may open doors to more honest conversations about what we can and cannot expect roadway and transit expansion projects to achieve. Acknowledging the limitations of both roadway and transit capacity expansion may also renew dialogues about road pricing — the congestion relief policy preferred by just 7% of the public and 8% of students — that presents the only viable long-term policy solution to mitigate traffic congestion among those explored here.

Shifting perceptions permanently may open doors to more honest conversations about what we can and cannot expect roadway and transit expansion projects to achieve.

Call to action #3: Update our teaching about induced demand

As we’ve shown, almost all planning students, and most engineering students, already understand that expanding road capacity will not alleviate traffic congestion. Transportation instructors should build on this foundation to ensure that students also understand the implications of transit expansion and congestion pricing. Given the widespread misunderstanding among the public, instructors should also challenge students to communicate their knowledge with the public. A straightforward assignment is for students to practice informing and persuading friends and family members about class topics. Ultimately, students could work toward communicating induced demand informally to the public via videos, social media, and accessible prose, and more formally with decision-makers via presentations and written memos.

Conclusion

Transportation professionals interested in reform face difficult odds. The public is woefully misinformed about induced demand — even those who appear to understand it at first blush may not fully grasp the concept. Correcting this misunderstanding may help increase public support for transportation reform. Please join us in being evangelical about induced demand. We have a lot of work to do.