Cashing Out Employer-Paid Parking

22 words that could change the American commute.

Federal, state, and local governments are trying to reduce air pollution, traffic congestion, and carbon emissions. One thing standing in the way is the federal income tax exemption for employer-paid parking. If your employer pays for your parking at work, then the value of the parking subsidy is not taxable income. Its equivalent cash value, in contrast, would be taxable. Put another way, if as part of your job you get $2,000 worth of free parking every year as a fringe benefit, that value isn’t taxed. If you walk to work and get an extra $2,000 in wages, that value is taxed.

Most tax exemptions for fringe benefits, like the one for employer-paid health insurance, promote a public purpose. But the tax exemption for employer-paid parking promotes solo driving to work, which conflicts with many public goals. Tax-exempt parking subsidies help explain why 81% of American commuters drive to work alone.

Most tax exemptions for fringe benefits, like the one for employer-paid health insurance, promote a public purpose. But the tax exemption for employer-paid parking promotes solo driving to work, which conflicts with many public goals.

Because free parking at work is a popular fringe benefit, repealing its tax exemption is unlikely. But that doesn’t mean nothing can be done. A small tweak to the tax exemption could make a big difference. Free parking at work should be tax-exempt only if commuters who do not drive to work are offered a benefit of equivalent value. Called parking cash out, this policy is politically feasible because it doesn’t take anything away from commuters who drive to work. Instead, it creates a new benefit for commuters who do not drive to work.

Employer-paid parking doesn’t treat all commuters equally. A driver gets a subsidy, while someone who walks or cycles does not. Free parking or nothing is not a fair deal. Parking cash out remedies this inequity and treats all commuters equally, regardless of how they get to work. It leaves the tax-exempt parking benefit in place but gives commuters more control over it. Commuters can drive to work alone and park free or use the parking subsidy’s value for any other purpose they choose.

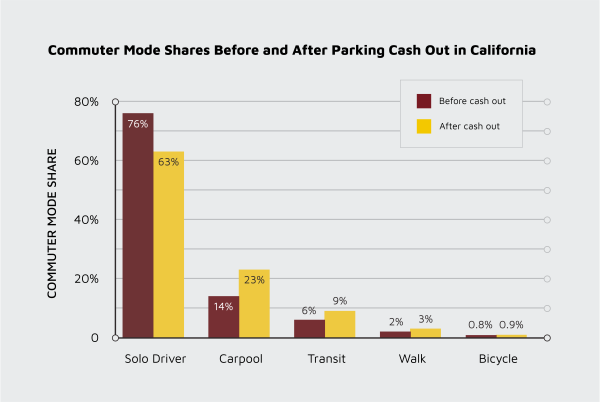

Parking cash out increases travel options for commuters, but will it change their travel behavior? California adopted a law requiring parking cash out in 1992, and a study of commuters who were offered the cash option showed striking results. Solo driving fell 17%, carpooling increased 64%, transit ridership increased 50%, and walking or biking increased 39%. Collectively, these changes reduced vehicle travel to work by 12%, which is equivalent to removing one of every eight cars from the road to and from work. Vehicle travel to work declined by 652 miles per employee per year, and CO2 emissions fell by 800 pounds. Employers reported that parking cash out was simple, fair, and easy to manage. It also helped to recruit and retain workers.

Figure 1. Commuter mode shares before and after parking cash-out in California

In 2020, Washington, D.C., adopted a similar law, the Transportation Benefits Equity Amendment. Employers who have 20 or more employees and subsidize parking for drivers must offer an equal benefit to commuters who get to work without a car.

Parking cash out is flexible. For example, some commuters might convert the parking subsidy into a tax-exempt pension contribution. Others might take the parking subsidy in taxable cash and put it toward renting an apartment within walking, biking, or scooter distance to work.

Parking cash out is cheap for employers in California and Washington because their cash-out laws apply only to parking spaces an employer rents from a third party (for example, a doctor’s office that rents space in the garage of a medical building). When a commuter cashes out a free parking space, money the employer previously spent to rent it becomes the commuter’s cash allowance, and the firm breaks even.

Other cities and states could pass similar laws, but adoption would be slow and cumbersome. Our proposed change to the Internal Revenue Code is a more straightforward way to ensure that employers offer parking cash out. Here is the code’s definition of employer-paid parking that qualifies for a tax exemption, and our proposed 22-word amendment is in bold:

Section 132(f)(5)(C): QUALIFIED PARKING – The term “qualified parking” means parking provided to an employee on or near the business premises of the employer . . . if the employer offers the employee the option to receive, in lieu of the parking, the fair market value of the parking.

As in California and Washington, the federal cash-out requirement could apply only to parking spaces that employers rent rather than own. Employers who oppose parking cash out will have to defend their right to subsidize only drivers — at taxpayers’ expense.

Because cash in lieu of a tax-exempt parking space becomes taxable income, parking cash out will increase tax revenue. The California study described above estimated that federal income tax revenue rose by $48 a year per employee offered cash out. State income tax revenue increased by $17 a year per employee.

Free parking or nothing is not a fair deal. Parking cash out remedies this inequity and treats all commuters equally, regardless of how they get to work.

Here’s how it works. Suppose a firm pays $100 a month per space to provide free parking at work. Commuters in the 25% marginal tax bracket who cash out the $100 tax-exempt parking subsidy receive $100 in cash, which is then reported as taxable wages. Of this $100, the commuter gets $75 after taxes, so those who cash out their free parking show that they prefer $75 in cash to a free parking space that costs the firm $100. This voluntary choice produces an extra $25 in tax revenue, and the windfall comes from increased economic efficiency, not higher tax rates.

Parking cash out will improve employee benefits without significantly increasing employers’ costs and increase tax revenue without raising tax rates. It will also increase transit ridership, reduce traffic congestion, conserve energy, improve air quality, and reduce carbon emissions. All these benefits will come from adding 22 words to the Internal Revenue Code.